Federal Immigration Raids Occur in N.C.

S.C. Senate's abortion bill fails in a subcommittee meeting

It's Friday, November 21, 2025 and in this morning's issue we're covering: As immigration raids descend on Triangle, focus turns to protecting children from trauma, Would Charlotte crime justify deploying National Guard?, N.C. Office of Recovery and Resiliency So Poorly Managed That State Auditor Couldn’t Determine Full Extent of Waste, Losing Money Every Month: Growing Finance Crisis Threatens Affordable Housing, Martinsville council rejects mediation for EEOC complaint brought by former city manager, Mississippi opioid settlement council members favor own organizations for grants, The Ongoing Psychological Toll of the Uvalde School Shooting, Tulane protesters allege TUPD violence, university denies wrongdoing, As Hamtramck, Michigan, awaits election results, city clerk is told to stay away, New Bern eye surgeon’s challenge of NC law could upend how health care facilities are regulated, Puerto Rico helped fuel America’s corn boom. Some locals see an unfair arrangement.

Media outlets and others featured: NC Newsline, Carolina Public Press, South Carolina Daily Gazette, Inside Climate News, THE CITY, Cardinal News, Mississippi Today, MindSite News, Verite News, Votebeat, North Carolina Health News, Investigate Midwest.

As immigration raids descend on Triangle, focus turns to protecting children from trauma

by Clayton Henkel, NC Newsline

November 19, 2025

The Wake County Public School System released data Wednesday showing how student enrollment has been affected by the federal immigration crackdown that began in the Triangle Tuesday.

While no immigration enforcement activities were reported at any of its campuses, the system recorded 19,471 absences on Nov. 18. That means nearly 11% of students in the district opted not to attend school on Tuesday, an increase of 7,841 absences above baseline data the school district examined. That represents a 67% jump in absences over an average day.

More than 110 schools in the district reported an absence rate above 10% on Tuesday, according to Lisa Luten, the chief communications officer for Wake County Schools.

Raleigh’s Baileywick Elementary School saw one of the steepest declines in attendance, dropping from nearly 91% on Monday to 68% on Tuesday with 161 children absent.

School administrators, teachers, and support teams are now actively reaching out to families across the district to ensure students stay connected to their classrooms, Luten said.

Anxious NC students ask how to respond

The news forced parent Amanda Paoloni to have a difficult conversation with her 14-year-old daughter this week. The 8th grader had seen stories about the U.S. Border Patrol crisscrossing North Carolina. She asked what she should do if her best friend were approached or taken by unidentifiable armed and masked men.

Paoloni said she knew her daughter’s best friend is of Mexican descent, but never once thought about her immigration status or that of her parents.

“What I do know is, she is kind. Quick with a smile, encourages my daughter to read, and laughs at her jokes,” Paoloni said at the Wake County School Board meeting Tuesday evening.

Wake County parent Amanda Paoloni. (Photo: WCPSS video stream)

Paoloni said she did her best to explain in simple terms that a teenager would grasp how to best manage her fear and adrenaline while being the most help in the moment.

But her daughter had so many other questions.

How do we know these people are ICE?

Why aren’t they identifying themselves?

What happens if they aren’t ICE?

How is this legal?

When the teenager said there was no way she would let an unidentified masked man take her best friend without a fight, Paoloni was scared.

“I looked at her and I said, ‘If you enter a physical altercation, you will lose,'” she told the school board.

Paoloni said this was not a conversation about learning, but rather a conversation about survival.

Wake Co. School Board member Christina Gordon (Photo: WCPSS video stream)

“Children cannot learn when they are in survival mode. Fear destroys the conditions required for student achievement: focus, memory, emotional regulation and a sense of safety,” said Paoloni.

Board member Christina Gordon, who has three children in Wake County’s public schools, acknowledged having a similar conversation with her own boys about the fear created by the threat of ICE enforcement.

“When fear enters our classrooms, it disrupts everything for everyone,” said Gordon, who has taught in both Wake and Durham County public schools. “I want to be clear, our commitment is to students, not to systems that destabilize their wellbeing.”

School board member Lynn Edmonds called the presence of masked federal agents a form of domestic terrorism.

“The presence of ICE, whether it’s here in Wake County or elsewhere, causes real, unnecessary and long-term trauma,” said Edmonds.

No one during Tuesday’s open comment period spoke publicly in support of the stepped up enforcement effort.

Immigration raids and learning loss

Long before the border patrol enforcement, Wake County’s school leaders made improving consistent attendance a top goal. Missing just two days a month can add up to more than two weeks of lost learning each year, according to information on the school district’s website.

Irene Godinez is the executive director of Poder NC Action, a nonprofit group advocating for immigrant rights, and the mother of a 9-year-old in the Wake school system. (Photo: WCPSS video)

A recent study by Stanford University finds immigration raids in communities with large immigrant populations have resulted in increased student absenteeism. The study found that even when the raids lasted just a few days, school absenteeism remained elevated for several weeks.

Irene Godinez, executive director of Poder NC Action, a nonprofit group advocating for immigrant rights, is the mother of a 9-year-old student in the Wake school system. She said the toxic stress caused by these unpredictable, unannounced raids goes well beyond learning loss.

“One in four children in the U.S. live in mixed-status families. Even U.S. citizens and children carry the constant fear that a parent may be taken from them,” she cautioned.

Godinez pointed to the case of a Durham 13-year-old who died by suicide in late February after being bullied about her family’s immigration status.

Godinez also urged school board members to adopt a non-punitive attendance policy during this immigration enforcement surge.

“Realistically, families experiencing terror cannot be burdened with proactively advocating for their child to be excused from class, not when they are protecting themselves from being hunted,” Godinez said.

Superintendent Robert P. Taylor has said the school district honors all laws protecting the privacy of Wake children and will remain focused on the well-being and education of every student, regardless of their background.

The Wake County Public School System has issued the following resources for parents and caregivers:

- How to talk to children about difficult news

- Helping children cope: tips for parents and caregivers

- How to talk to kids about stressful situations

- Supporting children in politically charged times

- Information on reporting absences.

NC Newsline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. NC Newsline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Laura Leslie for questions: info@ncnewsline.com.

Would Charlotte crime justify deploying National Guard?

by Lucas Thomae, Carolina Public Press

November 17, 2025

Is crime getting worse in Charlotte? It’s a simple question that’s trickier to answer than one might think.

On the whole, no, crime rates in North Carolina’s largest city are down compared to last year. But homicides in Uptown Charlotte, the city’s central business district which includes banking headquarters, sports arenas, night clubs and transit hubs, is at its highest point since at least 2015.

The city has faced extreme scrutiny in the months since Iryna Zarutska’s murder on Charlotte’s light rail transit system in August, which has since escalated into calls for deployment of the National Guard to assist with policing.

[Subscribe for FREE to Carolina Public Press’ daily and weekend roundup newsletters.]

Zarutska, a 23-year-old Ukrainian refugee, became a rallying point for Republicans concerned about crime in America’s cities, President Donald Trump among them, whose administration is fighting multiple legal battles over his deployment of National Guard troops to Portland and Chicago to support immigration crackdowns in those cities.

National Guardsmen were also activated in Memphis and Washington, D.C., earlier this year specifically to address crime.

North Carolina Gov. Josh Stein has dismissed the calls to activate the National Guard in Charlotte, which is, at least for now, enough to keep them out of the city.

“Local, well-trained law enforcement officers who live in and know their communities are best equipped to keep North Carolina neighborhoods safe, not military servicemembers,” Stein’s office said in a statement circulated to reporters.

Some pockets of Charlotte were also shaken this weekend by the U.S. Border Patrol, who made arrests across the city in an operation which the federal government said was targeted at undocumented migrants with criminal histories.

Immigration sweeps preceded the National Guard deployments to Los Angeles, Chicago and Portland.

Some seek National Guard deployment

It’s worth looking at how Charlotte got to this point, but sorting out the politics from the reality on the ground is difficult.

The firestorm surrounding Zarutska’s murder, compounded with an increase in homicides in Uptown (10 in 2025, compared to four last year), has created a narrative that the city is experiencing a “growing violence crisis,” as described in a Nov. 5 letter penned by Republican Congressmen Mark Harris, Pat Harrigan and Chuck Edwards, requesting that Stein dispatch the National Guard to assist CMPD with policing. Harrigan’s and Edwards’ districts do not include any of Charlotte, while Harris’ mostly rural district includes small portions of eastern Charlotte.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Fraternal Order of Police, a union that represents 1,690 CMPD officers, made the same request a month earlier in a letter addressed to Stein, Trump and Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles, a Democrat.

FOP President Daniel Redford attributed the uptick of violent crimes in Uptown to a “severe staffing crisis” within the department.

FOP has pressured the Charlotte City Council for years to increase pay and fund additional CMPD officer positions. According to Redford, the department has about 1,800 of 1,936 sworn officer positions filled, or about a 7% vacancy rate.

In an interview with Carolina Public Press, he defended FOP’s request for the National Guard from criticism that it was purely a political maneuver.

“If keeping our officers safe by having an adequate number of police officers and support personnel out there, I mean, if that's a political issue, then I think people need to revisit their view of politics,” he said.

“Because keeping our citizens safe and keeping police officers safe should not be a partisan issue.”

Prosecutors in Charlotte are also stretched thin, District Attorney Spencer Merriweather told CPP. The state legislature’s crime bill passed in the wake of Zarutska’s death funded 10 additional assistant district attorney positions for Mecklenburg County, but that still only brings the number of full-time prosecutors to half of what Merriweather thinks should be sufficient for a county of Mecklenburg’s size.

Too few prosecutors means that court calendars become backlogged and older criminal cases fall apart, allowing perpetrators to fall between the cracks.

“The issues that we face within our court system are problems of scale,” Merriweather said.

“Our job is to make sure that we’re not falling behind and that we’re meeting the public safety needs of our community, and as grateful as we are for the help that we’ve gotten, we’ve still got a long way to go.”

Addressing crime in Uptown Charlotte

Overall, crime is down in the city compared to last year, murders included, which CMPD celebrated in its most recent quarterly crime statistics report. But the data since 2020 shows a less positive picture, never consistently decreasing and instead remaining somewhere in the ballpark of 100 annually. To date, there’s been 83 homicides reported this year.

Most recently, CMPD announced it was investigating the death of 31-year-old Tanarus Tajuan Henry, who was shot and killed in Uptown Charlotte shortly after 11 p.m. on Friday.

The department has signaled that it is listening to the public’s concerns about crime, specifically in Uptown.

In October, the agency announced two new initiatives focused on policing in Charlotte's city center. The first was the re-establishment of the department’s defunct Entertainment District Unit, which is tasked with policing the areas around bars and nightclubs from 5 p.m. to 3 a.m.

The other is what the department calls the CROWN Culture Initiative (an acronym for Center City's Restoration of Order, Wellness and Nonviolence), which empowers officers to make arrests for what CMPD Captain Christian Wagner calls “quality of life” crimes: public urination, open alcohol containers and disorderly conduct.

As the top officer in CMPD’s Central Division, Wagner has overseen the implementation of these initiatives in Uptown Charlotte. So far, he said, they’ve been met with positive reception from the public.

The CROWN Culture Initiative strictly applies to a half-mile radius around Independence Square in the heart of the city, where Wagner said incidents involving police and resident complaints were most common.

“Whatever the numbers say, the feeling that people have, their perception of crime, is really, really important,” Wagner said.

“What we wanted to do is enhance the perception of safety and quality of life in Uptown by strictly enforcing statutes and ordinances that directly contribute to that sense of unlawful disorder.”

He added that officers are trained to connect individuals experiencing homelessness or mental health crises – those who might be disproportionately arrested for such offenses under this initiative – with the appropriate resources.

Border Patrol operation muddies the picture

An extra layer of complexity is the commencement of U.S. Border Patrol operations in the city this past weekend.

Gregory Bovino, a senior official in the Border Patrol who led previous large-scale immigration enforcement operations in Los Angeles and Chicago this year, said on the social media platform X that his team arrested 81 undocumented immigrants in Charlotte on Saturday, many of whom had criminal histories.

Because of the lack of transparency by the federal government about its immigration operations, the supposed criminal histories of those arrested is difficult to verify.

Merriweather told CPP that while he doesn’t have comprehensive numbers, his prosecutor’s office does handle a “significant number” of criminal cases involving undocumented migrants, sometimes as perpetrators and sometimes as victims.

“What we try to look at is really just about the crime that’s been committed and what the impact on public safety is and meet that where it is,” he said.

Border Patrol is a separate agency from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, commonly abbreviated as ICE, although both are federal-level agencies within the Department of Homeland Security.

ICE has operated in Charlotte and elsewhere across the state long before this weekend, but Border Patrol’s presence so far away from a national border is unusual. Neither CMPD nor the Mecklenburg County Sheriff’s Office were a part of the planning or operations with Border Patrol, those agencies said.

Protests against federal immigration enforcement operations in several major cities across the country were the impetus for the federalization of the National Guard in those cities earlier this year.

City and state leaders in those places have sued the Trump Administration over those deployments, arguing that they were illegal, and federal judges so far have ruled in the local leaders’ favor. But the president has since appealed up to the U.S. Supreme Court, which has yet to weigh in on the matter.

UNC School of Law Professor Rick Su, who specializes in immigration law, told CPP that what happens in Charlotte could ultimately rely on how the Supreme Court rules.

“If violent protest ramps up in Charlotte, the administration will likely point to that in justifying deployment,” he said.

“But I suspect it wouldn't be really that big of a deal what happens in Charlotte as the major question on authority is what the Supreme Court will say.”

In a video message Sunday, Stein said he had been in regular contact with local law enforcement as Border Patrol operated in the city this weekend.

“Public safety is our top priority, and our well-trained local officers know their communities and are here for the long haul,” he said.

He commended Charlotteans for remaining peaceful while accusing the federal government of “stoking fear” rather than fixing a “broken” immigration system.

“Rather than fix it, the federal government continues to play politics with it,” he added.

Editor’s note: This is a developing story and will be updated.

This article first appeared on Carolina Public Press and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Senators reject SC abortion ban proposal touted as strictest nationwide

by Skylar Laird, SC Daily Gazette

November 19, 2025

COLUMBIA — A bill touted as making South Carolina’s abortion ban the strictest nationwide proved to be too extreme even for a panel packed with anti-abortion Republican legislators.

The proposal that received national attention over the last few months ultimately failed Tuesday with a 2-3 vote. Four of the panel’s six Republicans declined to vote on the bill itself, enabling the three Democrats to sink it.

A vote to outright reject a GOP-led bill is rare in the South Carolina Legislature. Usually, legislators let bills that lacks support quietly die at the subcommittee level by indefinitely delaying a vote — if there’s a hearing at all. But after a day-long public hearing last month and an hours-long meeting Tuesday didn’t sway the sponsor — who also happened to be the panel’s chairman — in at least changing sections opposed by some of the state’s most fervent abortion foes, the panel proceeded to an up-or-down vote.

And it showed the bill doesn’t stand a chance even among Republicans, said Senate Minority Leader Brad Hutto, D-Orangeburg.

“We just think the vast, vast, vast majority of South Carolinians are against this,” he said.

Supporters could still try to revive the legislation after the Legislature returns in January. But the bill’s failure to advance through a subcommittee led by the sponsor, Sen. Richard Cash of Anderson County, almost certainly means that would be futile. Even a co-sponsor on the panel couldn’t vote for it.

Dubbed the Unborn Child Protection Act, the bill would ban abortions from the moment a pregnancy is “clinically diagnosable.” (The odd wording is meant to avoid prohibiting emergency birth control or fertility treatments.)

All Republicans on the panel were generally OK with a near-total ban on abortion. And separate legislation that goes further than the state’s six-week ban that took effect in August 2023 could get traction next year.

But what went too far in Cash’s bill for most Republicans were sections that criminalized women for getting an abortion, removed all exceptions for victims of rape or incest, and made it illegal to even advise someone on how to get an abortion elsewhere.

Anti-abortion groups split over proposal that could make SC’s ban the strictest nationwide

Attempted changes

The bill would allow women to be sent to prison for up to 30 years for an abortion. It also would allow her own relatives to sue her.

That was too much even for co-sponsoring Sen. Billy Garrett, who tried to delete that section. When his amendment failed 4-5, the Greenwood Republican proposed capping the punishment at two years in prison or a $1,000 fine, unless the woman who received the abortion agreed to testify in court against the person who performed it.

But that failed 4-4, with Cash noting his bill already gave women immunity from prosecution if they agreed to testify.

Garrett ultimately was among the four who didn’t vote.

“This world needs more love than hate,” he said. “This world needs more forgiveness than hate. And we’ve got to work toward that.”

Sen. Tom Fernandez spoke through tears about the possibility that his wife or one of his six daughters could end up imprisoned under the law.

“I cannot see women be put in jail,” said the Summerville Republican. “I can’t. If we’re going to sit here and continue to talk about women as if they were the worst creatures on earth, I might as well say that to all six of my girls.”

And yet, he was among the two Republicans who backed the bill in the final vote.

Taking out the punishment would “gut the bill,” Cash said. He contends the possibility of severe prison time or a potential lawsuit is needed to prevent women from getting abortion medication through the mail for an at-home abortion. That’s already illegal in South Carolina, though ordering the two pills online from providers in states with shield laws remains possible.

“How can you have a law that criminalizes some action and then say if you break the law, there’s no penalty?” Cash said. “It’s not even logical.”

Sen. Tom Corbin, R-Greenville, tried to remove a section making it illegal to even direct someone to a website providing information on getting an abortion.

Telling people what they can and can’t say would violate First Amendment free speech rights, Corbin said.

“It would break my heart if somebody tells somebody where to go get an abortion,” he said. “But I took an oath to uphold the Constitution of this country and this state, and I have a hard time supporting a bill with a section in it that basically says what you can and can’t talk to somebody about.”

Cash likened that section to laws against hiring a hitman to kill someone.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES.SUBSCRIBE

“You don’t have the right to provide information to someone on how to kill an innocent person,” Cash said.

Democrats voted against every amendment offered.

“You can’t make something bad better by voting for things, so we just voted against everything,” Hutto said.

Noting that South Carolina’s law already rates as among the nation’s most restrictive, he said, “To go any further is just an outright attack on women and doctors.”

Doctors would face 30 years in prison and loss of their medical license under the bill. Opponents contend doctors’ fear of the existing six-week ban already delays emergency medical care for women. Threatening doctors with 30 years in prison will endanger women further, they testified.

“There are so many things in this bill that are flawed,” said Ronnie Sabb, D-Greeleyville.

Only one amendment passed, and it was Cash’s. It allowed someone to take a juvenile to another state for an abortion with parental permission. It also allowed doctors to refer patients to specialists in states where abortion is legal. And it removed a section requiring the resuscitation of premature stillborn babies after a doctor testified last month that doing so would be pointless and torturous.

Beyond Hutto and Sabb, the other Democrat voting “no” was Deon Tedder of Charleston. Beyond Garrett and Corbin, the other Republicans not voting were Jeff Zell of Sumter and Matt Leber of Johns Island.

YOU MAKE OUR WORK POSSIBLE.SUPPORT

SC Daily Gazette is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. SC Daily Gazette maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Seanna Adcox for questions: info@scdailygazette.com.

N.C. Office of Recovery and Resiliency So Poorly Managed That State Auditor Couldn’t Determine Full Extent of Waste

Also known as ReBuild NC, the agency wasn’t good at rebuilding, monitoring budgets, overseeing contractors or helping hurricane victims, many of whom were left living in motels for years while their homes were supposedly being rebuilt.

By Lisa Sorg

November 19, 2025

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

The story of the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency’s disaster response efforts was itself ”a disaster.”

That’s what State Auditor Dave Boliek, a Republican, concluded in a scathing 506-page report released Wednesday, detailing mismanagement that left thousands of Hurricane Matthew and Florence survivors without homes and living in motels for as long as four years.

“The unfortunate truth of this report is the response from North Carolina to Hurricanes Matthew and Florence was a disaster,” Boliek said in a press statement about an agency also known as ReBuild NC. “When government decides to focus on administrative procedures ahead of boots on the ground, hurricane victims get hurt.”

NCORR’s accounting and monitoring was so rife with errors, the state auditor could not determine the full extent of the waste. “We really wanted to be able to show a full financial accounting of everything that happened at NCORR,” Boliek said at a press conference. “But when we took a look at the finances, the time, energy and effort would have cost well over seven figures to bring in contractors to reconstruct a true budget. It wasn’t worth the taxpayers’ dollars.”

A legislative oversight committee will discuss the findings on Thursday at 10 a.m. at a meeting in Greenville. It will also be streamed online.

NCORR received $800 million in federal funds and, when that ran out, another $297 million in state appropriations earlier this year to help eastern North Carolinians return home after the historic storms. Hurricane Matthew occurred in October 2016, followed by Hurricane Florence in 2018.

Most of the money was to be used for the Homeowner Recovery Program, which pays for storm survivors’ houses to be repaired or rebuilt.

The auditor’s office made several key findings:

- NCORR “had no structured financial roadmap or ongoing budget monitoring,” according to the audit. Nearly $785 million in public funds was disbursed to vendors “without a single, reconciled source of financial truth or robust oversight.”

- NCORR did not consistently verify that the contractors performed the work they were paid for. Only one of six program administration contracts include benchmarks for performance.

- NCORR spent more than $25.4 million on design and implementation of the Salesforce platform, which tracked the progress and expenditures related to homeowner projects. But incomplete and inconsistent data in the Salesforce system “led to operational challenges and delayed recovery for many families,” the audit said.

- Homeowners had to navigate eight protracted steps before contractors hired by the state would rebuild or repair their homes. It took an average of four years for hurricane survivors to return home, far longer than the agency’s goal of 18 months. During that time the state covered the costs of motels and storage, expenses that totaled as much as $2.1 million per month.

The state legislature created NCORR after Hurricane Florence, in response to an earlier iteration of the agency that had also fumbled the recovery program.

However, NCORR mismanaged the program nearly from its inception. ReBuild NC failed to hold many contractors accountable for their work and awarded several lucrative contracts to one, Rescue Construction Solutions, which did not install most of its modular homes on time. Rescue consistently denied any wrongdoing.

At the time, the agency’s director, Laura Hogshead, attributed the delays primarily to the pandemic. Hogshead abruptly left her job a year ago, within days of a particularly combative legislative oversight hearing.

“NCORR spent a lot of time on process when their job should have been swinging hammers,” Boliek told reporters on Wednesday.

NCORR had hired an outside company to manage the Homeowner Recovery Program, according to the audit, for a flat fee of $480 per application per month, until an application was formally deemed ineligible in the system.

That led to applications staying in the system—and generating income for the outside company—longer than necessary. When the contractor was managing the Homeowner Recovery Program, each project cost $41,000 in administrative costs, according to the audit. After NCORR brought the management in-house, the cost decreased to just $4,100 per project.

“NCORR staff reported that many applications could have been determined ineligible almost

immediately, but previous NCORR management instructed staff not to send ineligibility

notifications or close cases,” the audit says. “This lack of timely communication forced families to wait unnecessarily, preventing them from seeking alternative solutions for their housing needs.”

But problems persisted and even worsened after the pandemic. NCORR moved money among programs that short-changed some initiatives or eliminated them altogether, state records show.

“They had a pot of money and they spent it,” Boliek said. “They took the attitude that we’re going to spend it and when we’re out, then the program’s over. They didn’t spend money on a mission-oriented project with measurable incremental goals.”

As of Nov. 14, there were 314 households still waiting for new or repaired homes under the Hurricane Matthew or Florence programs, according to state data. More than 3,900 have been completed.

NCORR is expected to finish all projects and disband by October 2026.

In a written response to the auditor, Pryor Gibson, who replaced Hogshead as NCORR director, did not dispute the findings. He wrote that in partnership with the Office of State Budget and Management, the agency has “significantly improved its financial management systems to ensure the program can complete its work and close out in accordance with statutory timelines.

NCORR continues to implement process improvements with regards to strengthening vendor

management, local governments, and construction vendors.”

The auditor’s report is the latest probe into NCORR, state records show.

NCORR lost track of storm survivors who might have been eligible for uniform relocation assistance, according to a September 2024 monitoring report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Such funds help people who are displaced from homes as the result of federally funded projects, such as residents of public housing communities that were damaged by the hurricanes.

In February 2025, three months after Hogshead’s departure, NCORR officials were discovering a more chaotic financial situation than previously known, according to emails obtained under public records law. In some cases, NCORR had incorrectly spent funds on administration expenses for Hurricane Florence that were “in no way affiliated with Florence,” a state compliance specialist wrote, according to emails obtained under public records law.

Officials were also moving money between classifications and programs to cover an $11 million shortfall to rebuild or repair hurricane-damaged homes.

Other expenses were smaller, but suggest a lack of financial oversight: The office was still paying basic charges for state-issued cell phones for several former employees. Other cell phone expenses were being misclassified.

“If we’re not allocating properly, it would be a finding,” wrote Amanda Stapleton, NCORR chief policy officer, in March 2025. “Unfortunately things weren’t done 100% correctly in the past but, I believe we are still here because we want to do things right and successfully fix what we can. This is a good place to implement a change and fix it going forward.”

Federally funded projects have strict accounting protocols. If grant recipients violate those standards, the federal government can recoup the funds. That happened in August, when the U.S. Treasury requested that NCORR repay the federal government more than $800,000 in pandemic-related housing assistance funds that had been disbursed to ineligible households.

North Carolina had received more than $900 million in federal funds during the pandemic for its Housing Opportunities and Prevention of Evictions (HOPE) program. It was part of a $46 billion congressional appropriation to states, territories and local and tribal governments to financially assist eligible households and landlords with rent, utilities and other expenses incurred as a result of the pandemic. Hogshead was also in charge of the HOPE program.

The Treasury Department found NCORR, using HOPE funds, had erroneously paid more than a dozen landlords, people posing as landlords and members of a suspected fraud operation involving a married couple and a limited liability corporation owned by the wife.

The state disagreed with the Treasury Department’s findings and asserted that the payments were eligible at the time, based on federal guidance. It asked Treasury officials to “recognize the good faith compliance described above and reconsider its recoupment demand.”

NCORR could not be immediately reached about whether the amount has been repaid.

Losing Money Every Month: Growing Finance Crisis Threatens Affordable Housing

Landlords who run subsidized buildings say the numbers increasingly don’t add up — and that a rent freeze will put their tenants in a more precarious position.

by Greg David Nov. 19, 2025, 5:00 a.m.

BronxProGroup manages 93 subsidized apartment buildings containing more than 3,300 affordable apartments, mostly in The Bronx.

One in three units are in buildings where this year expenses are greater than the rents collected. And one in five are in buildings in such poor financial shape that the owners will have to resort to renegotiate their loans to lower their risk of defaulting.

CEO Samantha Magistro, who joined the family-owned firm about 25 years ago, says half of the units are in buildings that no longer can make any payments to their owners.

The business of running this kind of housing, increasingly, isn’t a viable one.

These buildings are not only rent regulated, but were also built with requirements that the apartments be leased at very low rents to people with very specific low incomes. Since the pandemic, their costs have risen a lot, their rent increases have lagged badly, and rent collections have slipped. Owners and managers say Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdan’s promise of an at least four-year rent freeze will make their situation worse.

“My father, who founded the company’s parent decades ago, would tell you things were worse in the 1970s,” the 43-year-old said, when areas of the Bronx saw widespread arson and abandonment. “But for my generation this is the hardest it has ever been.”

Magistro’s story is being repeated throughout New York City in this crucial sector of the city’s housing stock, according to two new reports on the all-affordable housing sector released last month, estimated to include about 300,000 units.

For the tenants in those buildings, this is the only housing they can afford. Without some change in course, possible future scenarios are grim: If housing stock deteriorates, or buildings are abandoned by owners, or investors are unwilling to put their money into affordable housing because the numbers don’t add up, the city’s affordability crisis will get even worse.

“What our report demonstrated is that financial strain in our affordable housing stock is not limited to a few owners, or specific geographies, or building types,” said Patrick Boyle, senior policy director at Enterprise Community Partners, an organization that helps arrange housing financing and works with BronxProGroup. “It’s widespread, and as advocates and policymakers, we urgently need to turn our attention to preservation.”

The search is on for solutions.

“There is no one easy fix,” Boyle added. “Increasing resources like rental assistance, reducing regulatory barriers and tackling expenses head-on will all be required.”

These all-affordable projects are built under agreements with either the city or state that dictate who can rent the units by income. Most are financed in part by low income housing tax credits. Industry experts estimate that about half are built and run by non-profits and the other half by for-profit developers like BronxProGroup, which specialize in this area.

Many of them rely on other forms of subsidy like federal or city vouchers to make their numbers work. Those programs tie rents to a fraction of the household incomes of tenants and pay property owners the difference.

About six in 10 affordable projects that have received financing help from Enterprise and the National Equity Fund have expenses that exceed their income, according to a report the group issued last month. Those projects have seen their expenses increase 40% since 2017, far more than the increases in rents allowed by the city’s Rent Guidelines Board, which sets rent levels for regulated apartments.

The Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, a coalition of community groups including nonprofit affordable housing organizations, found that about half of the all-affordable buildings it studied — containing 112,000 apartments — are losing money.

Previously, discussion of the plight of landlords has centered on owners of older buildings whose units are almost entirely rent regulated and whose finances have been badly hurt by 2019 changes in the rent laws. A key change effectively ended the ability of landlords to renovate vacant apartments and then charge a much higher rent, which helped them keep up with cost increases even when regulated rent increases for existing tenants were zero. (Rent freezes for regulated units happened three times during the de Blasio administration, in 2015, 2016 and 2020.)

This has led to a crisis for older buildings where virtually all the apartments remain rent regulated, which has been detailed by the Furman Center and stories in THE CITY.

Tenant advocates focus on the role of speculators who bought rent-regulated buildings at inflated prices assuming they would raise the rents dramatically over time.

But BronxProGroup’s affordable buildings never saw that kind of speculation and illustrate how the financials of a much broader group of buildings are increasingly untenable.

“They are a great example of a family-owned and operated business who are doing this because they believe we need more affordable housing in the city,” said Carlina Rivera, a former Council member from Lower Manhattan who is now chief executive of the New York State Association for Affordable Housing, which works with for-profit developers. “And they are telling you they are barely breaking even.”

The Enterprise study found that collections for the buildings it studied now equal only 90% of the expected rent, down from about 95% before the pandemic. These buildings were financed with the assumption that collections would be 95%.

“I call them workouts because I can’t afford my expenses and my mortgages even at 95%,” said Magistro. Prior to 2019, she was collecting 98%. This year she is collecting 93% which is higher than in 2022 and 2023.

Both Enterprise and ANHD zeroed in on increases in the cost of insurance, utilities and maintenance as the second major part of the problem.

Magistro’s insurance costs, which have gone up the most in The Bronx where her portfolio is concentrated, have jumped from $600 a unit annually to $1,600 since 2019.

Another key issue for her is paying overtime to staff, in part as a result of changes to trash collection rules that now force building workers to put out the garbage at night.

Both Enterprise and ANHD note that when building finances are strained, landlords have no choice but to defer maintenance, which leads to a deterioration of the housing stock.

Magistro this year laid off 10 staffers reducing her workforce to 143.

One of her buildings shows how the factors undermine a buildings’ finances.

She is collecting only 81% of the possible rent at a 30-unit building at Mapes Avenue in the Bronx, built in 2021. Her insurance has almost doubled since the building opened to $2,500 annually. She will need an infusion of cash to reduce the mortgage if the building is to operate for the long term and avoid default.

“Small projects have little resiliency to economic shocks like a spike in insurance,” she said.

Mayor-elect Mamdani has promised to help landlords reduce their costs to cope with his planned rent freeze. One key target will be reform of the city’s property tax system, which levies the highest taxes on rental buildings.

However, most of the all-affordable projects don’t pay property taxes. And other mayors have tried and failed to make headway on property tax reform, a thorny and complicated issue that needs Albany’s involvement to get done.

He also says he will make changes to the bureaucracy that will help. Magistro notes that when one of her apartments becomes vacant, it takes an average of five months for the city to approve a new tenant if a city subsidy is involved, which costs her lost rent for that period. Eviction of a tenant who is not paying their rent averages 12 to 16 months to conclude, in large part because of the sluggish workings of Housing Court.

ANHD wants the state to establish a fund for forgivable loans to help stabilize the finances of these buildings, increase voucher and other rental assistance programs, have the state intervene in the insurance markets to lower costs and provide new financing to help with rehabilitation programs.

Enterprise also calls for emergency funding, more rental assistance and actions to reduce insurance costs. It also wants sped up leasing for vacancies. Enterprise says in its report that solutions “cannot come on the backs of renters.”

Magistro can’t count on any of that now that property management is at best break-even. So she’s crafted a five-year plan in which her company will seek to increase its role as a developer, using the development fees she receives to keep the company afloat.

And with so much talk about the need to build new housing to solve the city’s housing crisis, she has a plea to Mamdani and other officials about their priorities and how to view landlords like her.

“There was a lot of work in previous decades to create and it is important to remain it stays financially feasible and it is important for the city to keep it affordable and preserved.” she said.

And she added, “Yes I am a developer and a landlord but I see myself as an employer,” she said. “I live in New York City. I choose to be in business in The Bronx. My office is in The Bronx. Seventy percent of the people I employ are from The Bronx. That’s part of the story, too.”

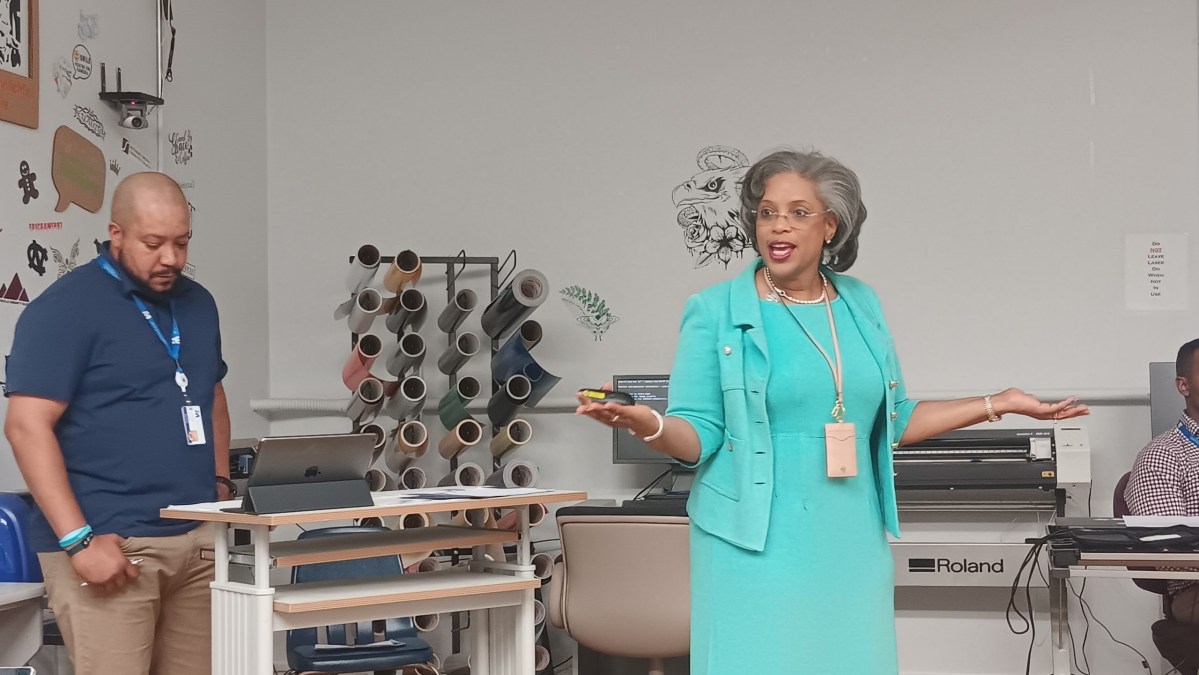

Martinsville council rejects mediation for EEOC complaint brought by former city manager

With mediation off the table, an attorney for Aretha Ferrell-Benavides said she intends to move forward with a lawsuit.

by Dean-Paul Stephens November 18, 2025

Legal proceedings stemming from former City Manager Aretha Ferrell-Benavides’ complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission against the city will continue, after the Martinsville City Council decided not to participate in mediation in the case.

Council members confirmed that EEOC mediation was discussed at a Nov. 12 closed meeting. They took no action following the closed session, and they declined to provide details about the discussion.

On Friday evening, Councilmember Aaron Rawls said he feels the council made the right decision and he is fine with moving forward in the EEOC process, outside of mediation.

“I support the EEOC process and look forward to receiving their findings,” Rawls said.

Mediation is an alternative to a traditional lawsuit in which both parties have the chance to speak with an EEOC-appointed arbitrator. The arbitrator listens to the details of a particular case from both sides.

Mediation allows parties involved in a dispute to avoid lengthy court battles.

The city fired Ferrell-Benavides in August. In the month prior to her termination, Ferrell-Benavides filed an EEOC complaint against the city.

The complaint alleges discrimination on the basis of gender and race. At the same time as the EEOC filing, there were a number of city-related controversies, including spending concerns and a federal civil rights suit brought by Councilor Aaron Rawls against Ferrell-Benavides stemming from a March incident at a council meeting.

Ferrell-Benavides maintains that she was fired in retaliation for filing the EEOC complaint.

Paul Goldman, an attorney for Ferrell-Benavides, said that his side was open to mediation.

“The mediation option is gone,” Goldman said.

If the city had opted to move forward with mediation, the session would have been held on Monday, according to Goldman.

With mediation off the table, Goldman said his client intends to move forward with a lawsuit.

“Now that there is no mediation we have to choose to sue or not,” Goldman said, adding that while his team has the option to not move the case forward, they do intend to press the matter to its conclusion.

Goldman said that next steps include waiting for a letter from the EEOC to give the go-ahead to either pursue or forego further legal action. Goldman said that letter could come sometime within the next six months.

‘Not how funding decisions are supposed to be made’: Mississippi opioid settlement council members favor own organizations for grants

by Allen Siegler November 18, 2025

Wake up informed. Sign up for our free daily newsletter and join over 35,000 Mississippians who start their day with Mississippi Today.

In a rectangle of desks outlined by some of the most powerful Mississippians, Andy Taggart took control of the conversation.

The former candidate for state attorney general is a member of the Mississippi Opioid Settlement Fund Advisory Council, and he speaks frequently at meetings. The group will recommend how lawmakers should spend hundreds of millions of lawsuit settlement dollars earmarked for preventing more drug overdose deaths.

On that November afternoon in the Mississippi Supreme Court building, as the group discussed how the state should spend up to roughly $100 million, Taggart preemptively asked for forgiveness for monopolizing the conversation. But he had a question for Dr. Dan Edney, head of the Mississippi State Department of Health.

Edney, a co-chair of the council, sat across the room from Taggart. The Health Department submitted one of 126 applications requesting money, which were reviewed by one of the council’s eight subcommittees.

“I was on the prevention and treatment subcommittee that gave a very high score to the Department of Health project,” Taggart told the council members. The agency asked for about $5 million to expand addiction treatment in rural areas.

Taggart and his subcommittee colleagues scored the application one tier below the proposals most highly recommended to be funded. He seemed surprised to learn it wasn’t in the highest category.

“Maybe it is Tier 2,” Taggart said. “I gave you a high score, Dr. Edney.”

“Thank you,” Edney responded as other council members burst into laughter – the type of jesting common among people who work closely together. Knowing that the tiers and project recommendations were yet to be finalized, Taggart continued.

“My question is, can you help us better understand it?” he asked Edney. “I was impressed, because I knew the heart of what was intended. But I don’t know the mechanics of what was intended.”

Edney obliged, and went into further details about the project.

The opportunity to explain his application demonstrates one of the advantages of being an opioid settlement council member who represents an organization requesting part of the settlement money.

Just one floor below where the state’s most difficult legal questions are argued in front of state Supreme Court justices, multiple council members who represent opioid settlement applicants used time to further explain why proposals they closely work with deserved funding.

Those opportunities weren’t extended to applicants who didn’t have council representation, at least at the Nov. 3 meeting.

“That’s problematic,” Greg Spore, a state public defender and opioid settlement council member, said after the meeting. “Who’s lobbying for them?”

Of the roughly $142 million requested from applications scored in the top two tiers, over $94 million was sought by organizations with representatives who serve on the council.

When asked after the meeting about his back-and-forth with Taggart, Edney said he was not and will not be involved in scoring his department’s opioid settlement applications.

“I was answering questions that were posed to me,” he told Mississippi Today.

Taggart, who has for decades been involved in state Republican politics, said he deferred all public comments related to the council to its chair and vice-chairs — Attorney General Lynn Fitch, Department of Mental Health Executive Director Wendy Bailey, and Edney. Fitch’s office declined to speak on behalf of Taggart, and Edney and Bailey didn’t respond to Taggart’s email.

The council, only a few months old, adopted a rule over the summer that prevents its members from voting on applications they’re closely associated with. But Matthew Steffey, a Mississippi College School of Law professor, said members have other avenues to lobby for projects they consider important.

Adopting rules that prohibit applicants from voting on their own applications is the absolute minimum ethical standard, Steffey said. It would be stronger, he said, to require applicants to leave the room whenever their applications are being discussed by the council.

“Most of the persuasion happens before the vote,” Steffey said.

Michelle Williams, Fitch’s chief of staff, said in an email to Mississippi Today that the council is made up of leaders from a variety of backgrounds related to addressing substance use disorder.

“These are also the people who may be best able to use the funds to continue their work responding to the opioid crisis for Mississippi and it would disadvantage the State’s response to prohibit them from applying,” Williams wrote.

he added that many council members sought clarification from applicants throughout the review process, but she did not provide examples. Neither Fitch nor Williams answered Mississippi Today’s question asking whether the attorney general believes the council needs stronger rules on ethics.

Edney said he can’t speak to whether the process has been fair to applicants who don’t have council representation. Bailey echoed Williams’ sentiment in an email, saying it was always likely that council members would also be applicants.

Two of the Department of Mental Health’s three opioid settlement applications received the highest grades of the 126 proposals. Bailey said she is always open to reviewing and strengthening procedures to improve the council’s fairness and public confidence.

“We all share the same commitment to accountability and integrity in how these funds are allocated,” she said.

The council is set to meet again on Dec. 2, and members are expected to further discuss the applications ranked in the top two tiers and other applications the council flagged at the last meeting. The group is required by state law to finalize recommendations for the Legislature by Dec. 7 — 30 days before the start of 2026 regular legislative session.

Spore, the public defender, said he wishes many applicants ranked in lower tiers could further explain their proposals to the council so they could share why their aims are important and unique.

One of them was Grace House in Jackson, which offers affordable sober living as women recover from addictions. Spore said when he worked for the Hinds County Public Defender’s Office, one of his clients entered the program as a condition of receiving probation.

“She completed the program there, and she was thriving,” he said.

Grace House applied for $600,000 to create more treatment options for women who’ve recently finished intensive addiction rehabilitation. Stacey Howard, its executive director, said many Jackson-area programs that provided these services have shuttered in recent years because of funding challenges.

The council scored Grace House’s application in the third tier, and the proposal is unlikely to be discussed at the next meeting. Howard said she has received no information about why her organization received the grade it did.

Because the secondary program was aimed at people without health insurance, she thinks a rejected grant proposal would be a loss for the most financially vulnerable Mississippians.

“If you’ve got money, then you can afford to go places, even out of state if you need to, to get treatment,” Howard said.

Brittany Denson, the sober living home’s operations coordinator and former Grace House participant, said on-the-ground organizations like hers have important knowledge on the prevention, treatment and recovery needs — information the Department of Mental Health has said the state doesn’t have a comprehensive handle on. The settlement money could be an opportunity to further act on that knowledge.

But she hasn’t seen Mississippi fund these types of efforts in the past, which makes her skeptical of the council’s aims.

“Of course, it’s unfair,” she said. “But that’s expected.”

‘We all have to have well-established practice’

Last spring, the Legislature instructed the settlement council to establish its members, solicit and review grant proposals and recommend to lawmakers which applications should be funded – all in the span of eight months. After multiple delays this summer, ranging from missing application materials to a cybersecurity hack, the committee released its application in August.

Groups had six weeks to read grant materials, develop an idea and fill out the application. Stacey Riley, chief executive officer for the Gulf Coast Center for Nonviolence, said the timeline felt rushed.

The center has a vending machine for naloxone, the opioid overdose-reversing medication, and works to address addiction among survivors of domestic violence. The application Riley submitted proposed a partnership between her organization and four others that serve South Mississippi communities — one that would expand trauma-informed addiction treatment, address other basic needs of those struggling with substance use disorder and work to address community stigma about drug use.

The application had a typo that resulted in final miscalculations of annual costs and total requests. But the two lines above the final calculation show the correct cost amount, according to a Mississippi Today review.

When the council released application grades a few hours before the Nov. 3 meeting, Riley found her proposal listed under “Incomplete Proposals.” The council’s document said the application had “facial deficiencies in the project budget.”

In a recent email to the council members, Fitch’s office said the application’s miscalculated budget figures is the reason why the Gulf Coast Center’s is listed as incomplete.

But he told the other members he was concerned about that application being scored below other applicants. He said he thought nearly no other applicants had as much hands-on time addressing substance use disorder as drug court employees.

“And yet they’re in Tier 2,” he said.

Minutes later, Taggart said he would like to see the courts’ application moved to the highest tier. Shortly after, Randolph called on the courts office’s director of intervention and treatment courts, Pam Holmes, from the audience to clarify council members’ questions.

“That’s not how funding decisions are supposed to be made,” Riley said when asked about the interaction. “We all have to have well-established practices that we do not engage in anything that even looks like a conflict of interest.”

After the meeting, Randolph told Mississippi Today that making sure these funds are spent appropriately is important to him, and it’s hard to know whether that will happen years down the line if private nonprofits get money. He said that won’t happen with the drug court application because of strict judicial oversight.

He also cited a pamphlet produced by the state judiciary office that says such courts have saved Mississippi taxpayers nearly $1.8 billion over 20 years, mostly by diverting people from prisons and jails.

“Any money that runs through the drug court is accounted for because we control it,” Randolph said.

Randolph also said not every council member pitched their proposal. Hattiesburg recovery advocate James Moore, whose son Jeffery died of an overdose, worked on a roughly $86,000 application to help fund and improve the weekly bike rides he hosts for those in addiction recovery. It scored in the second-lowest tier.

After the meeting, Moore said his application was so far down the list that he didn’t know whether bringing it up would have made a difference. But he also said it didn’t feel right to make an argument for his project when other organizations in similar situations didn’t have that opportunity.

Riley said that if she had the opportunity to ask the committee questions about the review of her application, she would have. But the center doesn’t have a representative on the council.

The Administrative Office of Courts, however, did have a representative who could clarify its request for roughly $61 million to provide more financial assistance for its drug courts — the most money any applicant asked for. Fitch, Bailey and Edney reviewed that application and scored it in the second-highest tier, recommending only partial funding.

Early in the first November meeting, Mississippi Supreme Court Chief Justice and council member Michael Randolph said he and the other judges didn’t score the Administrative Office of Courts’ application.

That decision could be costly. Moore said the account that funds his recovery rides and other efforts to prevent overdoses in the Pine Belt region, named in Jeffery’s honor, doesn’t have enough money to do much in the immediate future.

“I was asking for such a very small percentage of what’s available compared to what some of the other grants were seeking,” he said. “That was a little bit disheartening.”

Because Fitch allowed 30% of Mississippi opioid settlement funds to be spent on any public purpose, all of the national opioid settlement money the council oversees must be spent on one of the strategies the lawsuits list as addressing addiction. But unlike the applications from Moore, Grace House and Gulf Coast Center for Nonviolence, some proposals that will be further considered may not qualify.

Two proposals in the top two tiers seek funds for automated electronic defibrillators, purchases that aren’t very effective at responding to opioid overdoses because overdoses impact the respiratory system rather than the cardiovascular system. California’s state government has said AED purchases aren’t allowed by the settlements, and Pennsylvania’s says AEDs are not considered opioid remediation except in particular circumstances.

The Yazoo County Sheriff’s Department requested around $225,000 for license plate readers, tasers and two tablets. While the settlements’ lists mention some permitted uses for law enforcement, they’re focused on officer education and connecting people to treatment.

Fitch did not answer a question about whether she worried about Mississippi violating terms of the opioid settlement agreements. Williams reiterated that money the Legislature controls that isn’t overseen by the council can be spent on any public purpose.

In a recent email, Fitch’s office told council members that some projects that don’t qualify as addressing addiction “may be funded by the Legislature through a portion of the Fund.” But state law says money the Legislature oversees that doesn’t have to be used for addiction will be spent without recommendations from the council.

‘Once in a multi-generation opportunity’

Nabarun Dasgupta, a University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health senior scientist and recent MacArthur “Genius Grant” fellow, has used some of his state’s opioid settlement dollars to continue his lab’s work of determining what drugs are on the street and quickly getting that information to those most at risk of overdoses.

While that work is crucial, Dasgupta said it’s just as important to make sure the communities most impacted by the opioid epidemic — many of whom staff some of the small nonprofit organizations applying for dollars — get an opportunity to use this money. Those groups of people scarred by the epidemic will often be better positioned to make strides in ending the overdose crisis than the people in suits on Mississippi’s council, Dasgupta said.

“We sitting in offices and labs aren’t going to be the ones who do the last-mile outreach to get services where they need to go,” he said.

Without hearing from and investing in these last-mile providers, Dasgupta said he worries the money will be wasted — a disservice to those who’ve been suffering.

“This is a once in a multi-generation opportunity to address a longstanding social problem,” he said.

Denson, the Grace House operations coordinator, said the accountability she learned as a resident of the sober living home was crucial for her long-term recovery. She learned to cook for herself, got a job and felt like she became a productive member of society.

Organizations like Grace House have operated without opioid settlement funding for years, and Denson said she hopes that will continue even if the Legislature doesn’t invest in them. But she thinks discounting them for politically connected groups is a missed opportunity to end the public health crisis that has permanently taken many of her friends away.

“It’s going to kill people.”

Correction 11/18/2025: This story has been updated to reflect Dr. Dan Edney’s position as co-vice chair of the council.

‘That Day, I Died’: The Ongoing Psychological Toll of the Uvalde School Shooting

by Aitana Vargas, MindSite News

November 13, 2025

This project was produced with support from The Carter Center, the Economic Hardship Reporting Project , the Mesa Refuge, and the Commonwealth Fund, and co-published with Impremedia. A version of this work was republished in English by The Pulse (WHYY /NPR ).

Text and photos by Aitana Vargas

Warning: The content and descriptions in this report may be disturbing to some individuals. If you need emotional support, call or text 988, the Suicide Prevention and Crisis line, which offers free and confidential assistance 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

“I closed the door! I closed the door!” Amy Franco shouted from the hospital emergency room as she was being treated for an anxiety attack. That May 27, 2022, has been etched in this Latina's memory and spirit like a burden that will stay with her until her last breath.

Barely three days had passed since the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas — one of the deadliest ever to occur on U.S. soil. Franco had just watched a televised press conference during which an officer blamed her for leaving a school gate open, a charge later disproven by security camera footage.

In fact, Franco, who had only been working as an educator at the school for a month, had closed the door while rushing to warn staff and students about the presence of a gunman on the premises. But the accusations from law enforcement had already caused irreparable damage.

“That day, I died,” Franco says.

More than three years have passed since Salvador Ramos, a former student at the center, killed 19 children and two teachers with an AR-15 rifle and wounded 17 others, and Franco is still struggling to find the Amy she was before the massacre. “It’s a mental, physical, and emotional battle,” she says.

Franco embodies the aftermath that mass shooting survivors often face on their long and lonely road to recovery, processing grief, trauma, depression, and other psychological and psychiatric disorders. Added to this are the daunting and endless bureaucratic hurdles to access government aid, the devastating economic consequences of prolonged sick leave, and, in Franco's case, the loss of her home. But in Uvalde, the 77 minutes it took the shooter to wreak havoc also created deep fissures in the social fabric of this rural, majority-Latino community. Three years later, for some survivors and affected families, the twilight lingers on the horizon.

Located about 54 miles from the Mexican border, 26.3% of Uvalde's 15,300 residents live below the poverty line , a socioeconomic reality that became even more prominent after the massacre. The tragic shooting became a showcase for the systemic barriers the city had historically faced, including a lack of access to basic needs — such as clothing and shoes for some students — and a limited supply of psychotherapy services.

Franco's psychological and physical scars are palpable in her voice and body. When she recalls the security forces' unfounded accusations against her, her face tenses, and she tries to contain her tears and anger. "Did you hope that the attacker would kill me and that their version (of what happened) would be accepted as the truth?" she asks.

During the interview, Franco trembles uncontrollably. “Everything comes from that day,” she says. At home, she keeps the blinds and windows closed to preserve darkness. She fears going outside to take out the trash and collect the mail and often delegates these tasks to her children. She is undergoing treatment for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), depression, and anxiety, and she walks with the aid of a cane after suffering a foot injury the day of the attack.

Yet she was frequently denied workers' compensation insurance for her injures. "That's a battle in itself, and it's horrible," she laments. Even when insurance approves claims, "it's crazy how hard it is to find a doctor who will accept workers' compensation insurance," she says.

Over the past three years, Franco has seen several psychotherapists. “It’s sad because I would have liked to stay with the same one forever,” he says. And when he finally found one who specialized in EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) – a psychotherapeutic technique that helps patients process traumatic experiences – Franco had to abandon treatment because her insurance hadn’t paid the provider’s bills. For the past few months, she’s been receiving free psychological support through the Uvalde Juntos Resilience Center.

After the shooting, Franco never returned to her job. Eventually, she retired. Now 60 years old and in continuing physical decline, she relies on social assistance and her children to stay afloat. But the assistance is falling short: After the latest evaluation of her health, her employer's insurance cut her compensation from $487 to $315 a week, a decision that is causing her difficulties making ends meet, especially since she stopped living with her daughter a year and a half ago.

Despite the persistent financial problems, a glimmer of hope appears on the horizon. Franco is 89th on the waiting list for a program that provides rental assistance for a year. Although Franco's face fills with joy as she shares details about the program, it is underfunded, and it could take at least another year before she begins receiving payments.

Unlike other affected families, Franco embarked on a cumbersome bureaucratic process to apply for assistance from the Texas Attorney General's Crime Victims Assistance Program (CVC). For a year, she received checks. One day, they ran out.

“I applied for the second year thinking, 'OK, you know what? It'll help if I get (money).' But they sent me a check for $2,000 and told me, 'You've exceeded the amount of funds available to you,'” she says. Now she fears her workers' compensation insurance payments will also stop.

Double Victim: Bureaucratic Obstacles in Uvalde

Three years after the shooting, the lack of support and constant bureaucratic obstacles continue to remain insurmountable barriers for Franco. Not a day goes by that she doesn't wish she'd died at the hands of the attacker, she says. The emotional scars that haunt hier are as profound as the frustration she feels when she details the lack of centralized and coordinated efforts to ensure critical assistance to the survivors and affected families.

Despite the initial outpouring of aid from various agencies in the days and weeks following the shooting, chaos ensued in Uvalde, to the detriment of those affected. Most organizations disappeared from the scene within weeks. Franco didn't know where to turn for help, even though it was available. Nor did others.

According to statements from the Texas Department of State Health Services (HHSC) sent to this reporter via email, Texas made an initial disbursement of $5 million to the Uvalde Juntos Resilience Center to provide community services and crisis counseling. Additionally, Texas awarded $1.25 million to the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District (UCISD) to provide various mental health services to students and staff. School district officials canceled a scheduled on-site interview with this reporter, and the Uvalde City Council did not respond to multiple attempts to obtain their version of events.

Franco, however, says she had to learn to navigate the system independently, and word of mouth became an essential tool for learning about and accessing some of the services she needed. One day, someone told her about the generosity of Father Michael K. Marsh, and Franco went to St. Philip's Episcopal Church in Uvalde to ask for help. She needed money for gas and a doctor's appointment in San Antonio. When she stood up to shake Marsh's hand and he handed her a check, Franco was perplexed: "It was a $1,000 check." Franco used that money to pay for her rent. "I had to make sure I had a home," she says.

Despite the constant financial need and difficulties accessing medical services, Franco has been reluctant to seek help. “I don't feel comfortable because… I was raised with the belief that I have to work. You're supposed to be self-sufficient,” she says.

The Indestructible Wounds of Uvalde

It's a rainy morning when Father Marsh, who traded his career as a civil lawyer for the cassock in 2000, greets me with a smile in his office. The Texas clergyman articulates his thoughts and impressions eloquently, calmly, and with compassion. His face reflects concern for the well-being of his community and the pressing difficulties it is currently facing — challenges he believes will persist into the future.

Since the day of the massacre, Marsh has played a central role in providing spiritual support and financial assistance to the affected families, as has Sacred Heart Catholic Church and a group of volunteers from the Fire Department.

“I think many (impacted families) were already experiencing economic problems, and the shooting created even more problems,” Marsh says.

Marsh says that, until November 2022, his church used the generous donations it received from third parties to cover rent, food, and other bills for those affected — not medical expenses. The circumstances for which families requested assistance varied: from mothers who quit their jobs to homeschool their children, to families who, according to Marsh, couldn't get to work because they had medical appointments in San Antonio.

The shooter's family also benefited from Marsh's financial charity and understanding. After the shooting, the father lit 22 candles in tribute to all the lives lost that fateful day: 21 in memory of the children and teachers killed in Robb; the other in the name of the shooter. This latter decision, however, did not sit well with some members of the community.

“But who am I to exclude him (the shooter)?” Marsh asks. “I can't help but think about what exclusions he suffered throughout his life that may have contributed to this (the mass shooting).”

Despite his commitment, Marsh is concerned that money alone will not address the needs of a community that must heal its wounds and recover from tragedy. To truly recover, he says, it is crucial to create a space that allows for difficult and uncomfortable conversations about the loss of a loved one, grief, mourning, social fractures, conflict between different members of the community, as well as to learn to accept different experiences and perspectives about what happened.

According to Marsh, the lack of a community committee leading the response to the shooting has also contributed to the community's inability to regenerate from the tragedy. "(Groups) have emerged in isolation...but there hasn't been a centralized way to do it. Maybe it's not possible...but we all have a responsibility in this," he says.

The shooting, he continues, created deep divisions between families who lost a loved one and those with survivors. “There are so many broken hearts in so many places, and in so many different ways, that it’s hard to know where to begin… How do we begin to heal the wounds of the community?” he asks.

The attack, in turn, generated a climate of tension between those who defend police intervention and those who reject it. Adding to these conflicting feelings, Marsh says, is the fact that, while part of the community yearns to look to the future and put the tragedy in the past, this step is unfeasible for the vast majority of affected families.

“Healing is going to take decades,” he adds.

The massacre has also left an indelible emotional mark on the clergyman. It can be felt through his warm brown eyes, which overflow with tears when the pain becomes too acute. On the day of the shooting, Marsh went to the hospital and accompanied Gloria and Javier Cazares to identify their daughter, Jackie, who died on the way there. She was 9 years old.

“I was also asked to pray for a murdered child who couldn't be identified (initially) because he had been shot in the face,” he said.

Marsh's words and thoughts are filled with empathy and emanate from years of reflection. He also draws from his personal experience, since he knows firsthand the grief of losing a child. Fifteen years ago, his eldest son, Brandon , died in a work-related accident, and Marsh was forced to confront human mortality and the searing pain it instills within us when we face deaths that shatter — or regenerate — our faith in the existence of a higher being. For years, Marsh has been working with a spiritual guide who has helped him process his loss. He believes the community needs to confront and articulate its grief, but he acknowledges that doing so in public spaces may not be the most appropriate option for everyone affected.

“They are conversations that take place between two people or in small groups, because they are vulnerable conversations, and they are conversations from the heart, not the head,” he says.

“Protect Children, Not Guns”

One hot and humid morning, Marsh and I drive through the streets of Uvalde, some of which are covered with colorful murals honoring the victims. We first stop at the local cemetery. Then, we stop at Robb School. A black tarp covers part of the school's facade. The rest of the tarp hangs barely aloft, like an abandoned building. After getting out of the car, we walk toward the humble memorial that pays tribute to the victims. The passage of time and inclement weather have eroded the white wooden crosses, photographs, and some mementos of the victims. On each cross rests a bouquet of flowers: one of the few touches of color in this bleak scene. Marsh silently approaches each cross, pauses at each one, and observes them carefully. As he looks up, he sighs, and his watery eyes meet mine.

Three years after the massacre, the school is still a crime scene, Marsh explains. While the legal proceedings are being finalized, the school grounds are under police surveillance. As we walk through the area, a patrol car stops momentarily in front of us, and from the vehicle, an officer nods to Marsh. The police presenceand ongoing investigation are yet another open wound on this long path toward an uncertain future.

After a few minutes of reflection, Marsh approaches me and breaks the silence. His words take a political turn, questioning the almost unlimited right to bear arms in the United States and the impact they have on community security — or insecurity.

“We have more guns than people in the US,” he says. “What drives this need and desire to own them? … People say gun ownership isn't the problem, it's mental health. So why does the US have mental health problems that others don't…and we give them access to guns?”

This sentiment is also shared by some of the victims' families. A modest memorial to the students and teachers remains in the town square. Beneath a cross lies an orange-painted stone with a clear call to action: "Protect children, not guns."