Tensions Swell Over the Price of Parking in Wrightsville Beach, N.C.

Louisburg, N.C. leaders decry surprise election change passed without local input; Pennsylvania broke decades of promises to build a better system for people with mental illness; Mississippi broadband expansion moves forward despite federal changes.

It's Friday, August 1, 2025 and in this morning's issue we're covering: Rising parking prices creating tensions in Wrightsville Beach, Rural NC county sees rapid rise in unregulated care homes, Converting old NC furniture plant to paperware could bring jobs back to Graham County, Louisburg leaders decry surprise election change passed without local input, Older adults make up 1 in 5 suicides in Wisconsin. Here’s what can be done to fix that, Pennsylvania broke decades of promises to build a better system for people with mental illness. One mother's desperate fight to save her son shows the devastating consequences, SNAP use has declined in nearly every state. The program now faces its largest budget cut, Mississippi broadband expansion moves forward despite federal changes.

Media outlets and others featured: The Assembly, North Carolina Health News, Carolina Public Press, N.C. Newsline, Wisconsin Watch, Spotlight PA, Investigate Midwest, Mississippi Today.

The popular, easy-to-reach beach says charging for parking pays for services that benefit beach-goers. Surfers and other locals say it’s intensifying the region’s class divide.

by Kaylie Saidin July 25, 2025

On an evening this spring, every seat in Wrightsville Beach’s town hall was filled with people in blue shirts. Even standing room was limited.

Some attendees were smiling, others were stoic. Some carried handmade signs that read “Community over cash” and “Nature shouldn’t come with a meter.” Others were more provocative: “We know this isn’t really about parking.”

The group had gathered to present the aldermen with a petition advocating for free parking after 5 p.m. on weekdays.

Visitors must pay to park everywhere on the tiny island strip of beach from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m., March through October. It costs $6 an hour in the town-owned parking lots, or $5 an hour for metered street parking. Earlier this year, the town raised prices for day passes to $30 or $35 depending on where you park, a $5 increase over last summer.

Tensions over parking have emerged between the town and local beachgoers, particularly surfers in recent months. The dispute—which has also played out in other coastal North Carolina towns—is fueled by long-simmering class concerns in the Wilmington area, where some residents say beach access is eroding for lower-income people. Local leaders say they need the money to protect the beach and provide things like ocean lifeguards and sanitation services.

In 2019, street parking cost $3 an hour. Each increase has prompted pushback. In 2024, a petition calling for a reduced rate for locals received thousands of signatures.

Surf Mamas, which, as the name suggests, is a group for moms who surf, launched a petition this year for free parking in Wrightsville Beach after 5 p.m. on weekdays. As of late July, it had 13,906 signatures.

At the April meeting, the regional chapter of the Surfrider Foundation, a national group that advocates for equitable beach access, supported the free parking petition.

Jenna Haverstock, the president of local environmental nonprofit Plastic Ocean Project, told town officials that she has had difficulty finding volunteers for beach cleanups due to the fees.

“As someone who has completed and coordinated innumerable beach cleanups at no cost to the Wrightsville Beach community, paid parking is a barrier for us to get volunteers out here,” she said.

“It should not be a privilege to access the beach––it should be a right,” she said.

The board didn’t discuss the issue. They allowed three people to speak about parking during the public comment period, then moved on to the rest of the agenda. After the meeting, a town official told the group he had rejected their petition. The surfers say they plan to regroup.

The Bridge

Wrightsville Beach, while part of the greater Wilmington metropolitan area, is a separate town with its own mayor and municipal government.

Though the coastline boasts a variety of surf breaks, Wrightsville Beach is the most frequented for Wilmington surfers. This is primarily due to its proximity, just 8.5 miles from downtown and five miles from UNC Wilmington. It covers a mere 1.3 square miles and has a year-round population of about 2,500, but it’s a popular tourist destination. During peak season, the town sees more than 30,000 visitors a day.

Two bridges connect Harbor Island, where the elementary school and municipal complex are located, with the beach. The Heide Trask Drawbridge connects it to Wilmington. When that bridge is raised for boat crossings, traffic can back up for miles.

The most popular time to surf is from sunrise until 9 a.m., in part because of lighter winds and in part because it’s free to park then.

There are approximately 1,882 parking spaces available in Wrightsville Beach. Just one parking lot has free two-hour parking: at the town municipal complex, which is a mile from the beach and has signs to indicate that those spaces are not for beach parking.

This year, the town expects nearly $5.8 million in gross revenue from parking fees, though in past years revenue has exceeded its projections. The town administration and Board of Aldermen say money from parking helps support the town’s robust ocean lifeguard team, the police and fire departments, restroom maintenance, and litter collection.

Proponents of the paid parking program say that those services primarily benefit visitors and that the burden of providing them should not be placed solely on local homeowners.

“Providing a clean, safe, and sustainable beach requires extensive resources, most of which is the responsibility of the Town of Wrightsville Beach,” town manager Haynes Brigman said in an email. “Paid parking provides the Town an opportunity to recoup some of those costs from the actual users that are generating the need for the services.”

As one woman who has lived in Wrightsville Beach’s South End since the 1970s put it, visitors shouldn’t expect residents’ taxes to subsidize their beach experience. (She didn’t want to be named in the story because she feels there is a negative perception of residents from “in-town people.”)

The way she sees it, the enjoyment you get from the beach is similar to a day at a theme park or a movie theater, and those activities aren’t free.

Paid parking revenue also supports the town’s general fund, which the latest financial report says has “the necessary resources to recover from emergencies such as hurricanes, floods, or the recent pandemic.” Last year, the town also budgeted $1 million for beach renourishment, which adds sand to the coastline to fight erosion. (The most recent renourishment project, completed in March 2024, was federally funded, so some visitors note that their tax dollars already help protect the beach.)

State law bars most cities from using parking revenue for anything other than parking and traffic enforcement, but Wrightsville Beach received a statutory exemption in 1998. That has helped Wrightsville Beach keep property taxes at the lowest rate in the county. The median house in Wrightsville Beach is worth $1.5 million and the town’s tax rate was 9.23 cents per $100 in 2024, compared to Wilmington, where the median home value is $417,310 and the rate was 42 cents per $100.

In 2001, the exemption was updated to include “certain municipalities in New Hanover County.” Carolina Beach, Kure Beach, Surf City, Topsail, and Oak Island all have paid-parking programs now.

The closest beach to Wilmington with free parking is 30 miles away in Southport. (And that almost changed last month, but the town tabled a plan to charge for parking following local opposition.)

Before the 1940s, a trolley ran from the south end of Wrightsville Beach to downtown Wilmington, allowing citydwellers easy travel back and forth. The trolley cost 25 cents to ride, which included a bathing suit rental. But once highway construction began in the area in 1935, the trolley’s days were numbered.

Today, there is no public transit to the beach. Cape Fear Public Transportation Authority, also known as Wave Transit, has proposed municipal bus routes over the years, but Wrightsville Beach officials have repeatedly voted it down, citing concerns such as costs to the town.

The Country Club

Thaddeus Brown is a local engineer and surfer. As he sees it, the paid parking issue is emblematic of the class divide in the region.

In 2023, the median household income of Wilmington was $71,372, while Wrightsville Beach’s was $167,273, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The tensions that arise from this are evident in the local surf scene, Brown said. Wrightsville has a generally friendly surf culture compared to other places—it’s not crowded enough here to spark fist fights—but people can get edgy, especially during a bigger swell.

Brown grew up on Long Island and spent a summer mowing lawns to buy his first surfboard. The best surfers there, he said, were the ones who came from similar working-class backgrounds, and they fiercely protected their spot in the lineup. “The reason we are aggressive is because they have everything,” he said. He’s wary of signs of money in surfing, like name-brand board shorts and expensive boards.

“Wrightsville Beach is turning into a place where they don’t want regular people,” he said. (This sentiment was familiar—many surfers called it a wannabe Figure Eight Island or Hilton Head.) “My buddies and I used to joke: You can’t go to the beach if you’re poor no more.”

When it comes to local leaders and parking, he said, “To them, ‘oh, it’s a dollar more.’ … It’s turning the beach into a country club.”

Julimaria Cullins founded Surf Mamas, which now has more than 100 members, in 2020. She started the petition to allow free parking after 5 p.m. on weekdays in hopes that more locals could surf, or even just enjoy a beach walk after work. She said nearly a quarter of parking transactions last year came from residents of Wilmington or greater New Hanover County, according to data she obtained from Brigman, the town manager.

In addition to the petition, Cullins and fellow Surf Mamas Kaylan Ganus, KC Hackney, and Kelly Wolfe presented a formal proposal to town officials at the April board meeting. On May 23, Brigman told the group the town wasn’t planning any changes to the parking program. In an email to the Surf Mamas, he said letting go of that parking revenue would place an undue burden on taxpayers.

Now, Cullins believes the only way forward is through legislative change. She and her group plan to contact state representatives to challenge the town’s exemption on how parking revenue can be used.

This may be difficult. In 2021, after the town doubled hourly parking rates, locals created a petition to repeal the exemption. State Rep. Ted Davis Jr., who represents Wrightsville Beach, declined to support it, saying at the time, “This is a local issue and should be handled by the local governmental entities involved, and not by the State.”

Cullins doesn’t buy that the town needs the revenue. “The town is healthy financially,” she said. “We’ve seen the financial reports. This isn’t about their economic survival.”

“On the surface it’s about parking, but it’s much more than this,” she said. “It has always been a social equity issue. Marginalized groups—be it by income, age, or circumstance—are being pushed out of a public space that should belong to everyone.”

I’ve lived and surfed in the Wilmington area for six years, four of them on Wrightsville Beach. In my first few years here, I tutored students at New Hanover High School downtown. Several of them told me they’d never once been to the beach despite living here their whole lives.

“How would I get there, and how would I pay?” one high school junior told me. I was struck; I had been around his age when I first learned to surf and found solace from my teenage frustrations in the ocean.

North Carolina’s constitution embraces the public trust doctrine, a legal principle that holds the coastline as a natural resource preserved for public use. This doctrine has been upheld in court; for example, in 2016 the state Supreme Court dismissed a case in which Emerald Isle beachfront property owners tried to block the public from accessing the sand in front of their home. The sand from the water’s edge to the high-tide mark on the coastline is public land—you just have to be able to get there.

Peak Season

In interviews around town, residents—many of whom didn’t want to be quoted on a contentious local issue—had mixed feelings about the parking program. All of them talked about how much the town has changed in recent decades: more vehicle traffic, more tourists, and more municipal regulations.

Some supported paid parking because it helps fund their ocean lifeguard program, police department, and parks department. Others were critical, citing how difficult it is to have friends or family visit. Many said that public transit could help with traffic and parking concerns. One longtime resident described the seasonal beach traffic as a safety concern. During peak season, she said, the single-lane roads in town are so congested that emergency vehicles cannot easily get through.

Jeff DeGroote, an alderman and owner of South End Surf Shop, voted against the increase to the daily parking rate this year. He cited a negative effect on local businesses if parking costs drive away potential shoppers. “It’s already hard enough to operate down here, seeing that we’re a seasonal place,” DeGroote said.

Nancy Rose Vance, 77, grew up in an oceanfront house on East Asheville Street. Her father, Lawrence Rose, served as an alderman in the 1960s. Back then, her family raised beagles in the house and let them roam the beach. Now, the town bans dogs on the beach from April through September.

Frustrated by the parking situation, Vance posted on Facebook last month about giving her daughter and grandchildren rides to the beach so they can avoid both traffic and the parking fees.

“I think about working families with little children who deserve to go to a beautiful beach for a family day without having to spend that kind of money,” she said in an interview. “I think it’s obscene. Anybody living in the area who wants to go to a public beach with public access should be able to park, and I don’t think the cost of parking should be preventative.”

I went surfing one morning not too long ago, arriving shortly after sunrise. The parking lot was already packed with pick-up trucks and vans. People waxed their boards and drained the dregs of their coffee. The surf was summertime good—waist-high and clean. Cullins was out there. I saw her silhouette on the other side of the pier, amid a group of women catching waves.

At 8:45 a.m., the surfers started tapping their watches. These would be their last waves of the day. People left the beach, one by one, until only a handful were still in the water. The wind picked up and changed direction. The tide started to fill in.

I took my time getting out, hoping to get the perfect last wave. By the time I got back to my car, the parking lot was empty.

Rural NC county sees rapid rise in unregulated care homes

by Jaymie Baxley, North Carolina Health News

July 28, 2025

By Jaymie Baxley

In the winter of 2021, social workers in rural Wilson County were overwhelmed by a surge in reports of adults with disabilities being abused.

In a typical month, the county’s Department of Social Services receives about 30 such complaints. But that February, the agency fielded 33 reports in just seven days.

When Nichole Atkinson, manager of the department’s Adult and Family Services program, began to investigate, she noticed a common thread: The reports all originated from residences known as Multi-unit Assisted Housing with Services, or MUAHS.

Unlicensed and largely unregulated, the houses occupy a gray area in North Carolina’s long-term care system. They are broadly defined by state law as facilities where patients can choose their own service providers and where personal care is “arranged by housing management.”

That essentially makes them independent living settings — places where residents retain autonomy and are free to come and go, hire their own caregivers and manage their own finances. Yet many of the complaints received by Atkinson’s office described situations in which residents with behavioral health conditions were being denied access to their money, food stamps and medication — basic resources they were supposed to control themselves and have rights to.

After some digging, she learned that several MUAHS houses in Wilson County had been misleadingly advertised to residents’ families and doctors as assisted living communities, which in the public imagination can conjure up visions of dining rooms and plentiful recreation, along with assistance with health needs.

These facilities were anything but. Atkinson said MUAHS operators are only required to provide residents with a daily meal. In some houses, simple furnishings like bed frames are considered amenities.

But the deceptive advertising, she said, is technically allowed under state law, which confusingly classifies the houses as one of three types of “assisted living residence[es]” recognized in North Carolina.

The houses are not subject to routine inspections and monitoring like assisted living facilities, nor are their residents protected by the state’s Care Home Bill of Rights.

“These homes have no oversight,” Atkinson said. “No one is required to go in to make sure that they have proper zoning and proper construction, or that proper rules are in place. There’s no vetting of who owns or operates them.”

The hospital incident

In the years since that rash of reports, the houses have been a persistent problem in Wilson County.

Then came the hospital incident.

On the weekend of Aug. 12, 2023, a local MUAHS operator brought all 34 of his residents, all of whom had behavioral health issues, to the 20-bed emergency department of Wilson Medical Center.

Chris Munton, then CEO of the hospital, said the department’s emergency staff typically treat three to four behavioral health patients a day. It usually takes six more days, he said, to find a place that can provide those patients with an “appropriate level of care” after they’ve been discharged.

Hospital staff and administration scrambled to meet the needs of a large group of people with lots of needs. The influx of patients forced Wilson Medical Center to activate a special command center typically used during hurricanes and other natural disasters.

Munton said the patients were left at the hospital because the operator needed someone to feed them.

“It was discovered that an owner of multiple MUAHS in the area had gone out of town and did not have anyone to provide the required one meal a day for their residents,” he told the city council in Wilson, the county seat, during a June 2024 meeting. “To solve this dilemma, the owner brought all their residents to the ED.”

Chris Munton, former CEO of Wilson Medical Center, describes an incident involving a local MUAHS operator who dropped off 34 of his residents at the hospital’s emergency department.

The incident led to an audit that revealed more than 60 percent of all behavioral health patients seen at Wilson Medical Center from 2021 to 2023 had been residents of MUAHS houses. An “alarming” number of those patients had traveled from other states to live at the facilities, according to Munton.

Some MUAHS operators, he added, appeared to be using the hospital as a “holding station” for residents who “become too aggressive or unstable.”

“These patients often do not require immediate health care assistance but are left at our facility to alleviate unwanted disruption within the MUAHS house,” he said. “Without any accountability or guardrails to how these MUAHS operate, Wilson Medical Center is left to care for and find placement for these patients, even if they do not require emergency care.”

Munton left Wilson Medical Center less than two months after his remarks to the council. The hospital did not respond to written questions from NC Health News.

Unwitting epicenter

MUAHS houses have existed in the state since 2001, when the N.C. General Assembly passed legislation recognizing them as part of a broader effort to expand residential options for older adults and people with disabilities.

The goal was to provide a flexible model of care that would allow residents to live more independently than in traditional adult care homes or nursing facilities, while still having access to support services. These settings were intended for individuals capable of directing their own care, and the state placed fewer regulatory requirements on them than on licensed facilities.

Over time, however, the lack of oversight has made the houses a “regulatory black hole,” said Corye Dunn, head of public policy for Disability Rights North Carolina.

Unlike adult care homes, which must meet staffing and quality standards, MUAHS facilities operate with minimal state involvement.

“The state has very little power, but very vulnerable people are often housed there,” said Dunn, whose organization works with people who live at the facilities.

Kimberly Irvine, director of Wilson County DSS, said this regulatory gap, combined with growing demand for affordable housing and supportive care, has created a system ripe for abuse.

“This program was developed to be an alternative to more expensive, restrictive nursing home care,” she said. “But with the lack of regulations and [no] licensing requirement, that has kind of opened the door for people that want to exploit our disabled and elderly.”

https://public.flourish.studio/resources/embed.js

The number of MUAHS houses in North Carolina grew significantly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated the nation’s ongoing mental health crisis and intensified demand for community-based housing for people with disabilities. An NC Health News analysis found that just 87 of the state’s 141 registered houses were in business before 2020.

Wilson County, which had no MUAHS houses before the pandemic, has become the unwitting epicenter of that growth. Fourteen facilities have set up shop there over the past five years, more than any other county in the state over the same period.

And that’s just counting the ones that are registered. Irvine said several houses in the county — ranked as the state’s 25th most populous by the U.S. Census Bureau — are being run off the books with near impunity.

“Operating one of these facilities without being registered is the lowest misdemeanor with the lowest fine,” she said. “They're going to pay the fine and continue to operate, so there really is no penalty.”

Legislation signed into law by Gov. Josh Stein on June 27 makes failing to register a felony offense, with violators subject to a daily fine of $1,000. The new policy, which takes effect on Dec. 1, also allows state and county officials to inspect facilities that are believed to be operating without registration.

Behind closed doors

Atkinson, the DSS program manager, noted that some houses in Wilson County are “actually run properly.” But for reasons she and others don’t fully understand, the community has become a hot spot for unscrupulous operators.

Many of the so-called facilities in Wilson County are little more than aging single-family dwellings scattered across residential neighborhoods — indistinguishable from the homes around them.

The operators make their money, Atkinson said, by withholding residents’ Social Security benefits. They also claim any payments made to residents through the state’s Special Assistance In-Home program.

“The individuals are really not seeing any benefit from their Social Security check, in addition to their Special Assistance In-Home payment,” she said, adding that some operators collect as much as $1,900 a month per resident.

Dunn said she has seen operators charge “surprisingly high rental rates for surprisingly poor conditions with poor access to food and services.” The model is so profitable, she said, that the owners of licensed facilities with more oversight, such as family care or adult care homes, sometimes run MUAHS houses on the side.

“They recruit someone to the licensed facility and then after a while, if they’re the right profile, they let the person know, ‘Hey, there’s another opportunity and do you want to move in?’” Dunn said.

“These are options that are designed to extract as much money as possible from people with disabilities,” she added. “Once that bed opens up in that licensed facility, they have a pipeline of people to come in to the more profitable MUAHS.”

County social workers have documented troubling conditions inside the homes.

Atkinson recalled cases in which residents were found sleeping on bare mattresses placed directly on the floor. Some were living four or more to a room, crammed into tight quarters with no privacy.

An NC Health News review of incorporation filings and local tax records found that several houses in Wilson County are not even owned by the entities that operate them.

“We've had some encounters where we found out operators were renting from rental properties,” Atkinson confirmed. “During our evaluations, we learned that some of the landlords did not know that the properties were being used as businesses. They thought they were renting to one person.”

Wilson Mayor Carlton Stevens did not respond to messages seeking comment from NC Health News, but local elected officials have indicated they’re aware of the issue.

During the June 2024 board meeting, Councilman Donald Evans acknowledged that Wilson had been experiencing “problems with these facilities for quite some while.”

“They can move into any neighborhood, set up homes anywhere they want to without notifying anybody, and that’s a real problem that I have,” he said of the houses’ operators. “They should not be allowed to move anywhere they want to within our city without us having any control over it.

But the city’s hands were tied, Evans said, because the houses are authorized by the state.

‘Basic human standard’

As chairman of the board that oversees Wilson County's Department of Social Services, Dante Pittman is well acquainted with the community’s MUAHS predicament.

Last November, the 29-year-old Democrat was elected to represent the district that covers Wilson County in the N.C. House of Representatives, giving him a legislative platform to tackle the issue.

“I told our board that I'm tired of just talking about it,” he said in an interview with NC Health News. “It's time that we at least introduce some legislation and work with our partners at the state level.”

In April, Pittman filed a bill that seeks to enhance regulation of MUAHS houses. Among other things, it would prohibit the houses from being advertised as assisted living facilities and would ban operators from accepting residents with significant cognitive or functional impairments.

When discussing the proposed legislation with his fellow lawmakers, Pittman is quick to point out that he doesn’t want to eliminate the houses. His goal, he said, is simply to ensure they’re subject to some level of oversight.

“I’m careful when I speak with folks because I don't want them to think that I don't see housing, or the lack thereof, as a tremendous problem,” Pittman said. “I understand that, and I’m working with others to try to address it, but there's got to be a basic human standard that's a part of this solution.”

State Rep. Sarah Crawford (D-Raleigh) is co-sponsoring the bill. Outside of politics, she serves as CEO of TLC, a Wake County nonprofit, formerly known as the Tammy Lynn Center, that provides residential services to adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

“We're regulated by everybody and their brother, sister and second cousin,” she said of her organization. “We have many, many eyes on us, and we have to make sure that we're following all the rules because every individual deserves the right to live in a safe environment.”

Crawford doesn’t think the changes proposed in Pittman’s bill would harm MUAHS facilities that are being run the way they were originally intended to be. She said it might, at worst, create “some additional paperwork” for operators, but the burden “should be very minimal.”

“If they're doing the right thing, they shouldn't have any fear,” she said. “But we need to have a process for getting bad actors either out of the business or helping them make reformation so that they can provide better care.”

Once filed, though, the bill has not progressed at the legislature.

Stopping a spread

Most of the state’s MUAHS facilities are not run like the ones in Wilson County. In fact, they stand in stark contrast.

Cambridge Village Optimal Living has 422 units across three campuses in Wake and New Hanover counties, making it by far the largest MUAHS operator in North Carolina. The company’s newest site, The Cambridge at Brier Creek in Raleigh, has 132 one-bedroom and 63 two-bedroom units — the most of any facility registered with the state.

Its other facility in Wake County, Cambridge Village of Apex, is a 121-unit campus that has been registered since 2011. Cambridge Village of Wilmington, the site in New Hanover County, launched in 2017 with 106 units.

At each facility, residents have access to a wide range of amenities and on-site health care services from licensed providers.

But Cambridge, which did not respond to a request for comment from NC Health News, advertises the campuses as independent living communities, not assisted living settings. The company's website boasts of chef-driven restaurants, salons and heated swimming pools — a far cry from the houses in Wilson County, which don’t even have websites.

Nash County, which neighbors Wilson and is also represented by Pittman in the General Assembly, is home to 16 MUAHS facilities — the most of any county in the state. In an email to NC Health News, Denita DeVega, director of the Nash County Department of Social Services, said her office hasn’t “encountered any significant problems” with the houses there.

Pittman, however, believes it’s only a matter of time before the issues reported in Wilson County begin spreading to other communities.

"If it can happen here, it can happen anywhere," he said. "If we don't take care of this now, I'm afraid we will see it replicated all across our state."

Note: This article has been expanded from the original. It has also been updated to clarify that Disability Rights North Carolina has access to people living in MUAHS facilities.

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Converting old NC furniture plant to paperware could bring jobs back to Graham County

by Jane Winik Sartwell, Carolina Public Press

July 28, 2025

When Shaun Adams was laid off by Stanley Furniture in 2014, he was beyond frustrated. Not only was he losing his job at the furniture manufacturing plant, but Graham County was losing its largest employer and last major manufacturer.

In the year after Stanley left, the unemployment rate in Graham County rose to the highest across North Carolina. Adams’ frustration grew as he saw the Robbinsville facility lay almost entirely vacant for more than a decade. Why weren’t town and county officials courting another company to use the factory space and create more jobs?

Adams ran for mayor, determined to bring manufacturing jobs back to Robbinsville. He won the office in 2021.

[Subscribe for FREE to Carolina Public Press’ alerts and weekend roundup newsletters]

Last week, he got his wish: the Chinese biodegradable paperware company EcoKing announced an $80 million investment to reopen the same shuttered facility, promising 515 jobs in one of North Carolina's most economically distressed counties.

“We have lost so much population over the years because of factories closing and our low median income,” Adams told Carolina Public Press. “This means a lot of people will get to come home.”

EcoKing manufactures for fast food restaurants like Chipotle, Chick-Fil-A, and Panda Express. When the Robbinsville facility comes online in 2026, it will be the biggest employer in Graham County, providing an average wage of $46,700, nearly double the median individual income in the county.

Picking Graham County

But first, the abandoned Stanley plant needs major renovations — to the tune of $21 million.

“If you walked through the plant with me, you would say they ought to do a series of The Walking Dead here, because it just looked abandoned and neglected,” Robin Sargent, owner of Old Town Brokers, a firm that helped orchestrate the sale of the plant.

“At one time, it was a vibrant place, but holy cow, someone just let it go to hell. Taking the pictures was like getting it ready for a dating site. It takes a special person to be able to have a vision for a space like that.”

The facility needs major HVAC, plumbing and electrical work. But EcoKing wasn’t scared off by the state of the plant.

Partially they were wowed by Graham County’s natural beauty. Partially they were swayed because of the cheap, abundant power supply in the area.

The deciding factor, however, was incentives: between the town, the county and the state, EcoKing was offered $12 million over five years to pick Graham County instead of a site in the other Southern states they were eyeing.

EcoKing’s customers — those big name fast food restaurants — wanted paperware products made domestically. With the tariffs coming down from Washington, the company had to act quickly.

“The tariff is high,” John Lin, EcoKing’s representative for this project, told CPP. “And 80% of our customers are here in the United States. So is most of our raw material. That taught us to make a decision: we’re going to land right here, and be Made in the USA.”

Economic lifeline

The EcoKing investment is a lifeline for this Western corner of the state. Graham County once had more than 1,100 manufacturing jobs across four factories and a sawmill. Now all of that is gone.

After Stanley Furniture was the last to leave, a company called Oak Valley Hardwood occupied a small corner of the same building starting in 2016, but left when COVID hit. Other than that blip, hardly any economic investment has come to the area.

“For decades we struggled with the closing of textile plants and furniture plants and the tobacco industry being more or less sunset,” Sargent said.

“This area has just been hammered in a way that is not well understood — 500 jobs is a big deal here. This is a really great story of how we were able to capture the interest of an Asian company to launch a big investment in their industry here.”

There's a certain economic irony to EcoKing's investment. Many of the manufacturing jobs that left Graham County — and Western North Carolina more broadly — went to China as companies chased cheaper labor. Now, a Chinese company is bringing manufacturing back to the exact same building where American workers once made furniture.

EcoKing will use the same pulp supplier that served the Pactiv paper plant in Canton, whose 2023 closure resulted in the loss of 1,200 jobs and a lawsuit from former attorney general and current governor Josh Stein.

Bringing back Graham County workforce

The one downside of US manufacturing is the cost of labor, Lin said. In China, the company can get away with much lower wages. EcoKing plans to use some automated manufacturing to offset this inflated cost.

But still, the plant will need 515 workers. In one of the state’s smallest counties, that won’t happen overnight — it will require coordinated workforce development.

Hiring is projected to happen in two phases. The first phase will take place over the next three to five years, and create about 300 jobs. The second, on a longer timeline, will bring on 215 more. The company is partnering with Tri-County Community College and Western Carolina University for workforce development.

“We’re going to take a slow-burn approach,” Josh Carpenter, director of economic development group Mountain West Partnership, told CPP. “That’s what we did with Harrah’s Cherokee Casino: built a workforce of 900 to 1,200 over the years.”

Construction crews are already at work on the $21 million restoration. And for the first time in over a decade, Graham County has concrete reason for economic optimism.

This article first appeared on Carolina Public Press and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Louisburg leaders decry surprise election change passed without local input

by Ahmed Jallow, NC Newsline

July 30, 2025

Officials and residents from the town of Louisburg gathered Tuesday outside of the North Carolina Legislative Building to protest a surprise change to the town’s mayoral election process, which they say was made without their knowledge or any public input.

The provision was inserted into House Bill 183, which originally focused on wake surfing restrictions on Lake Glenville in Jackson County. But in a last-minute revision, lawmakers added a language that alters how Louisburg, a town in Franklin County, elects its mayor.

The change requires a runoff election if no candidate receives more than 50% of the vote. If only two candidates file for the office, however, the winner will be determined by a simple plurality. Town council elections will not be affected by the change and will continue to be decided by plurality.

The incumbent, Mayor Christopher Neal, said runoff elections create unnecessary burdens for voters, especially those with limited time and resources. He cited studies that have shown a significant drop in voter turnout for runoff elections, often with participation declining by 40% or more between the initial primary and the second round of voting.

“That puts a burden on seniors, single mothers, working people who have to take off and vote,” he said at the press conference.

Town leaders say they were not consulted and only learned of the provision after the bill had already passed both chambers of the legislature and became law on June 26.

Because the measure was a local bill applying only to specific jurisdictions, it did not require the governor’s signature to become law.

Neal questioned why the provision was added so late and by whom. He noted that the bill was sponsored by Rep. Mike Clampitt, R-Transylvania, whose district is more than 300 miles from Louisburg. A review of the recording of the House session on June 25 — the day the conference report containing the addition was adopted — revealed that no explanation was provided for the provision or the bill before it was voted on. The Senate does not archive recordings of its sessions.

“Only reason that I can come up with this bill being passed is because of Louisburg having an African American mayor… hopefully someone else can offer a much better [explanation],” Neal said. Neal is the only Black mayor in Franklin County.

Local leaders demanded transparency and answers from lawmakers about who pushed for the provision and why it was added without input from the community it affects.

Andrea Woodin, the Franklin County Democratic chair, called for “complete transparency” from Rep. Matthew Winslow, R-Franklin. “The voters deserve the whole story,” she said during the press conference. Winslow and Sen. Lisa Barnes — also a Republican — are the only two lawmakers who represent Franklin County in the legislature.

Newsline efforts to contact Reps. Clampitt and Winslow were unsuccessful.

“There’s a problem with people trying to turn municipality elections, which are supposed to be nonpartisan, into a partisan pony race,” said Deborah Maxwell, president of the North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP. “That is not fair.”

The town estimates runoff elections could cost between $7,000 and $10,000, which they say is a burden for a small municipality with limited resources. The Town Council has unanimously passed a resolution opposing the law. “They immediately understood what was going on. They immediately realized that this was done in the dead of night and that we would not want to have this,” Neal said.

Neal said they are exploring legal and legislative options to reverse the change and prevent similar measures from being pushed through without local consent.

Neal is running against two other people. The general election is scheduled for Oct. 7.

NC Newsline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. NC Newsline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Rob Schofield for questions: info@ncnewsline.com.

Older adults make up 1 in 5 suicides in Wisconsin. Here’s what can be done to fix that.

by Sreejita Patra / Wisconsin Watch

July 21, 2025

Editor's note: This story discusses suicide. If you or someone you know may be experiencing a mental health crisis, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing “988." Or you can send a text message to 988 or use the chat feature at 988lifeline.org.

Click here to read highlights from the story

- Older adults account for 1 in 5 suicides in Wisconsin, with the rate among men over 75 twice the statewide rate for everyone.

- The latest data from 2023 show suicide rates among older people declined over the previous year, when they were higher than the national average.

- The state budget includes additional mental health resources in the Fox Valley and for Winnebago Mental Health Institute in Oshkosh. Republican lawmakers are calling for additional telehealth resources, while Democrats want to reinstate the 48-hour waiting period for gun purchases.

Earl Lowrie doesn’t spend a day of retirement without thinking about suicide.

The disabled 66-year-old lives with two grandchildren in the village of Cameron in northwest Wisconsin, where he is $50,000 in debt and suffering from multiple autoimmune diseases. Nowadays, Lowrie spends his time trying to elude a pernicious voice, telling him “there really isn’t any recourse now” and to “take some opioids and go to sleep.”

Nationwide, adults over 65 have some of the highest suicide rates by age group, though they are among the least likely to seek or receive mental health support. They made up 20% of all suicide deaths in Wisconsin between 2018 and 2023 — but in 2023, only 3,142 older people used county mental health services, down from a peak of nearly 4,000 who used them in 2018.

Wisconsin Watch spoke to policymakers, health professionals, advocates and older adults about the current mental health landscape for older people in Wisconsin and the possible roads to geriatric suicide prevention in the future. Their goals beyond prevention are to help older adults realize that they are not forgotten and to raise awareness about community supports at every stage of life.

That’s what Lowrie is working to remember.

Older men kill themselves at two times the statewide rate

In 2023, 184 older Wisconsin adults ended their own lives, out of 921 total suicides. The statewide age-adjusted suicide rate was 15 out of 100,000 residents, while the rate for those between 65 and 74 years old was 15.7. Suicides among those 75 and older were higher at 17.1.

That’s down from the previous year, when Wisconsin adults above 65 died at a higher rate than the national average, 18.6 vs. 17.7. It’s unclear why the numbers went down or whether it will continue in future years.

Nonetheless, depression and anxiety disorders “have really picked up” recently for the patients of Kenneth Robbins, a geriatric psychiatrist based in Rock County. He has especially noticed issues with older men, who died from suicide at more than two times the statewide rate in 2023.

Robbins said that one of the biggest contributors to this suicide rate is isolation.

“What's unique about older white men is that many of them are not very socially adept,” Robbins said. “When they retire, they’re not quite sure what to do with their lives exactly and often become very lonely and feel like they’re not doing anything meaningful and start to wonder, ‘What’s the point of living?’”

Robbins also noted that older adults who struggle with medical problems, such as dementia or cancer, are highly likely to attempt suicide for fear of physical pain and becoming a “burden” to their loved ones.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, more than half of residents 55 years and older who died by suicide in 2023 had health problems that “appeared to have contributed to their deaths.”

Sen. Jesse James, R-Thorp, said he was at a wedding when his wife’s great-grandmother, suffering from dementia, told him to kill her. James’ father told him he would rather die by suicide than live with the disease.

“I’ve had many family members state they would rather die by suicide than to remain on the Earth if they were attacked by dementia,” said James, who worked to ensure the recently approved state budget included more mental health services in the Chippewa Valley.

Older adults in rural Wisconsin face extra challenges

Lowrie retired from truck driving in 2019 after he had a fall at work and needed a spinal fusion for his back. Around that time, he developed rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis, and later stage 4 cancer.

“My mental illness went off the rails,” he said. “The only reason that I didn’t (take my life) was because I’ve seen how painful it is for others around you.”

The pain Lowrie was referring to was the loss of his youngest son, Justin, who shot himself a little less than a decade ago. Ever since then Lowrie retreats for long periods into a depression “closet” that lets very few people inside.

“I’ve been trying to break out of that here more recently,” he said. “Often you don’t have that trigger that you needed to get you out of the closet to go out and find something that’s going to bring you out of this slump.”

Lowrie’s home county has an age-adjusted suicide rate lower than the statewide average, but many rural counties in the state have significantly higher than average rates. Of the 184 suicides among older adults in 2023, 115 were in areas with populations under 50,000 and 42 were in areas with populations under 10,000.

Older adults in rural areas often live far away from mental health providers, many of whom don’t accept Medicare, according to Robbins. They also often live far away from family and community.

“That further adds to the hopelessness you feel and the loneliness that you feel,” Robbins said. “Nobody’s noticing that you’re getting more and more depressed, and becoming less and less functional.”

No legislation geared toward geriatric mental health

Though there is no legislation circulating to address geriatric mental health and suicide prevention, legislators are pushing broader bills related to mental health, substance abuse and gun control, which they say will start to help.

Gov. Tony Evers’ initial 2025-27 state budget recommendations included $1.2 million and six full-time equivalent positions for Mendota Mental Health Institute’s geropsychiatric treatment unit, which serves mentally ill, disabled or drug-dependent older adults who require more specialized services than are generally available.

The request was for hiring additional staff and moving the unit to a nearby building with larger treatment space. Jennifer Miller, the communications specialist for Mendota, said the Wisconsin DHS made the request because it is seeing an increase in older patients who need mental health services.

With the new space, “there (would have been) additional capacity at (Mendota) to serve these individuals in a space designed to meet the unique mental health treatment and service needs facing an aging population,” Miller said.

However, legislative Republicans removed the additional funding for Mendota. Instead, the budget provides almost $16 million to address the current deficit at the Winnebago Mental Health Institute’s “civil patient treatment program” for 2025. Winnebago, located in Oshkosh, treats patients legally ordered to undergo mental health treatment, but the funding is not specifically for geriatrics.

The budget also includes $10 million in funding for the development of a mental health campus and $1 million for reopening a substance abuse treatment facility in the Chippewa Valley, which has a significantly higher suicide rate than the statewide average.

James and Rep. Clint Moses, R-Menomonie, who co-authored the provisions, said the campus will restore the region’s mental health beds lost after two nearby hospitals closed last year. Moses also said that he has been working on general telehealth bills that would help bridge gaps in mental health care for older adults in rural areas.

“It’s about making sure they’ve got access — (especially) if they don’t have family members — to someone they can talk to,” Moses said. He believes older adults should be able to do an online video meeting rather than drive 45 minutes or an hour to talk to someone about their issues.

For suicide prevention, Democrats have circulated multiple bills related to gun safety, one of which would reinstate the previous 48-hour mandatory handgun purchase waiting period repealed by Republicans in 2015.

Former Democratic state Rep. Jonathan Brostoff — who last year purchased a handgun and killed himself within hours — had argued for reinstating the waiting period, saying it had prevented his own previous suicide attempts.

Sen. Chris Larson, D-Milwaukee, a close friend of Brostoff who reintroduced the bill to the Senate in June, said the law had protected an “untold number of people.”

“There’s the false narrative of, ‘if you don’t have a gun, you’re not safe,’ right? … (But) the statistics show that most suicides that end in death are with a handgun,” Larson said. “The more time we can put in between the time that somebody is trying to obtain a handgun and when they actually get it, it saves lives.”

People 65 and older carry out 25% of all firearms suicides in Wisconsin and use firearms for suicide at by far the highest rate. Lowrie disagrees that gun legislation would prevent suicides and said older adults start to feel a “very large sense of helplessness” when their guns are taken away.

Finding community

Lowrie attributes suicide challenges and reluctance among older adults to seek mental health support to the way his generation was raised.

Organizations such as NewBridge, a Madison nonprofit dedicated to serving low-income older adults, seek to proactively address the issue by providing older adults with community programming and case management, but especially mental health care.

Kathleen Pater, the mental health manager at NewBridge, described older adults as a “forgotten group” who “might not be the best advocates for themselves.” Her team is often the first human interaction their clients have in a long time and the first to have honest conversations about mental health.

We need to “really focus and see the importance of this stage in life and how much seniors can really offer the community back,” Pater said. “It’s connecting them back into the community with intergenerational programs, and just a societal shift in seeing our elders as valuable and knowledgeable and having all this life experience rather than being isolated and forgotten.”

In January, Lowrie finally sought out help for his mental illness after an interaction with his ex-wife sent him into a “tailspin” of anxiety and suicidal thoughts. When an online artificial intelligence therapist didn’t work, his best friend Wes told him about the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Initially, Wes had suggested a NAMI chapter in Rice Lake, about seven miles away from his village. But Lowrie soon found the Rice Lake office was closed, and the nearest location in Eau Claire was 50 miles away.

Despite “talking (himself) into it and out of it above half a dozen times,” Lowrie took a leap of faith with the encouragement of Wes and his granddaughter and went to Eau Claire. He now describes NAMI as “a rope pulling me out of the water, keeping me from drowning.”

“There's people from every walk of life and every different kind of problem that you could imagine, but mine was no more twisted and weird than their own,” Lowrie said. “It was through them I found enough encouragement and ideas of finding more help.”

Through NAMI, Lowrie was connected to individual, weekly counseling, a nutritionist, a dietitian, and a mental health prescription that gives him hope. He continues to attend NAMI Eau Claire’s biweekly meetings, and his cancer is now in complete remission.

Despite newfound support, Lowrie said he is often “suffocated” by his mental illness and that most of the time, he would rather be dead than suffer. In his worst moments, not even his favorite things, like the laughter of children or the breeze on his skin, can draw him out.

But Lowrie doesn’t intend to stop fighting.

“I am going to do everything in my power to get to the other side of my mental illness,” Lowrie told Wisconsin Watch. “I’m on a mission, and I’m not holding back at all … I’m coming out the other side one way or another.”

If you or someone you know is in immediate physical danger, call 911.

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health crisis:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988 or Línea de Prevención del Suicidio y Crisis: 1-888-628-9454

- Call the National Hopeline Network: 1-800-784-2433

- Text the Crisis Text Line from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a crisis counselor: 741741

- Chat online: https://988lifeline.org/

- Contact a county crisis line: https://www.preventsuicidewi.org/county-crisis-lines

If you or someone you know needs general mental health support:

- Contact NAMI: https://www.nami.org/support-education/nami-helpline/

- Call NAMI Wisconsin: (608) 268-6000

- Call for information on community resources in Wisconsin: 211

Go to https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/mh/phlmhindex.htm

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The Cost of Failing

Pennsylvania broke decades of promises to build a better system for people with mental illness. One mother's desperate fight to save her son shows the devastating consequences.

July 28, 2025

by Danielle Ohl Investigative reporter

Sue, Robert, and Jonathan are pseudonyms. Their names and some details have been changed to protect their privacy.

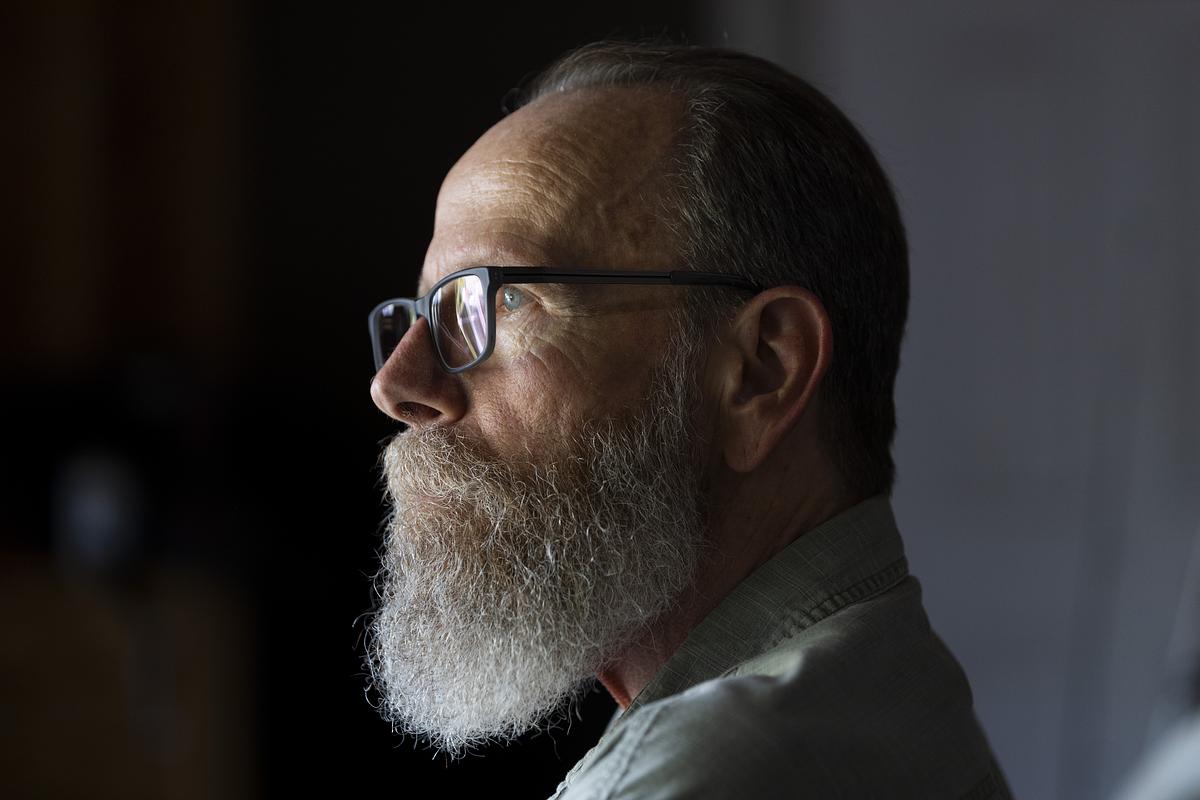

When Sue thinks back on that cold spring morning in 2022, there are things she knows and things she doesn’t.

She knows her son Robert, who has had a serious mental illness for nearly a decade, turned up half-naked at her mother’s house, freezing, and in the throes of psychosis. She doesn’t know where he’d been or how he got there.

She knows she drove him home, tried to get him to take a hot shower, and put on warm, clean clothes. She doesn’t know why he refused.

She knows Robert begged for help getting to the hospital because there was something wrong inside his head. She doesn’t know why, when a state trooper arrived, he changed his mind.

She knows that after hours of erratic behavior, Robert agreed to go to the hospital if they called for an ambulance. She doesn’t know why, when he saw it arrive, he went for the knife drawer.

She knows she threw her body across the kitchen island in time to stop her son from ending his life.

She doesn’t know if she made the right decision.

“I just play this over and over in my mind.

Maybe I shouldn’t have taken that knife out of his hand.”

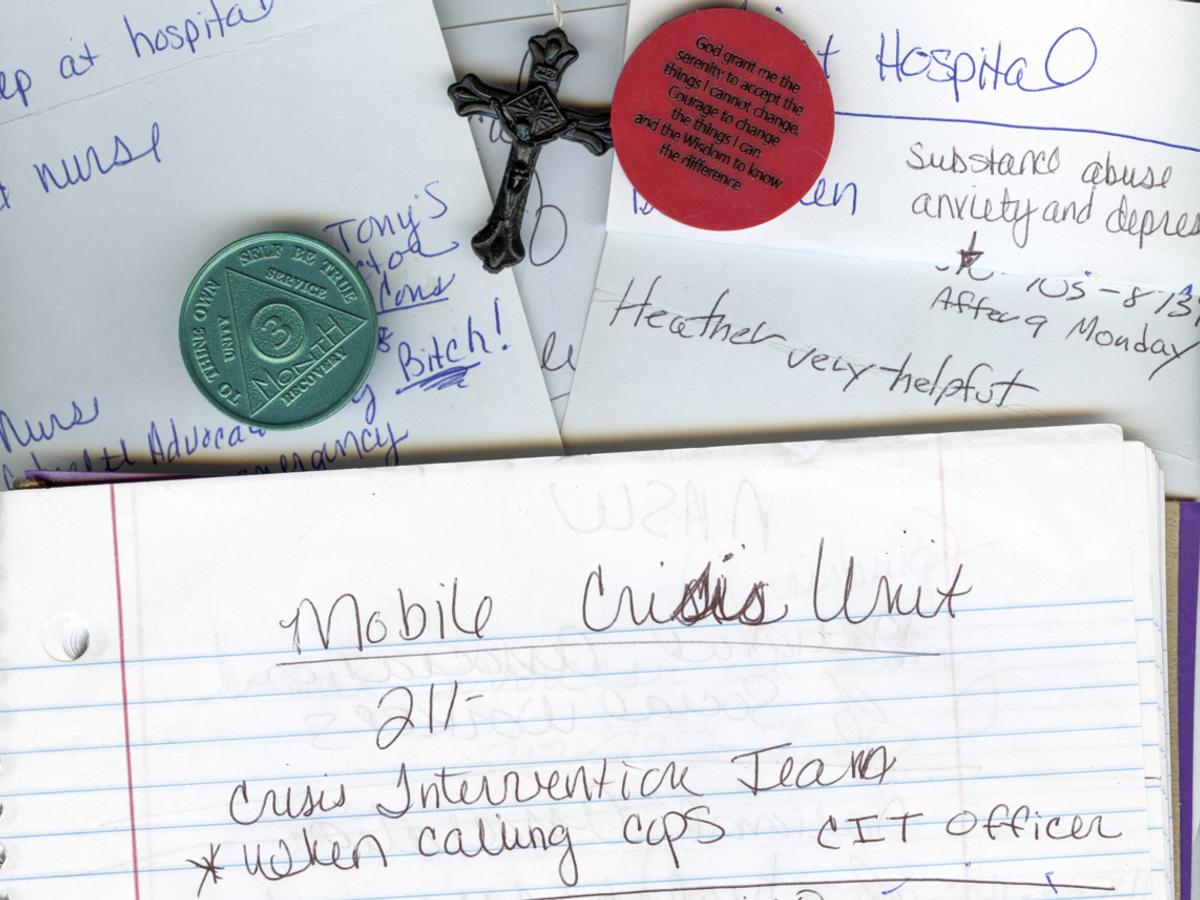

Handwriting excerpts throughout this story are from the notebook Sue uses to keep track of her attempts to get care for Robert.

By the time Robert was born in the mid-1990s, Pennsylvania had been closing its psychiatric hospitals for decades.

The hospitals provided intensive, publicly supported care for people with mental illnesses that were severe enough to interfere with everyday life.

But by the late 1980s, some had become notorious for violence and abuse. Inside these institutions, even people who did not experience headline-grabbing conditions could languish for months and sometimes years beyond what their treatment required.

Some never left.

Persistent stories of barbaric conditions and patient deaths at Philadelphia State Hospital prompted a state investigation and eventual closure under then-Gov. Bob Casey Sr. Speaking to reporters during a teleconference in 1987, Casey previewed what would become the consensus around Pennsylvania’s state hospitals over the next three decades.

“We are not going to put these people out on the streets,” Casey said. “But we can no longer tolerate packing them into little more than a warehouse. Neither option is acceptable to me, nor should it be to a caring and civilized society.”

Studies following closures at Philadelphia and Allegheny County’s Woodville State Hospital showed that patients enjoyed far better lives when receiving care in their communities than while institutionalized.

In 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this sentiment in Olmstead v L.C., requiring states to provide people with mental disabilities access to community-based care.

Just over a year later, a group of psychiatric patients sued Pennsylvania to win their promised care. Like the plaintiffs in Olmstead, they were eligible for community treatment but remained institutionalized.

A federal appeals court sided with the patients in 2004 and directed Pennsylvania to create a plan to release them. But a year later, the case was again in front of that court and the patients were still in the hospital.

In his ruling, appellate Judge Max Rosenn commended Pennsylvania for reducing the patient population from nearly 40,000 in the 1950s to just 3,000 in 2000. But his opinion was scathing in its assessment of the commonwealth’s plan to deinstitutionalize the rest of the state hospital system: It amounted to no plan at all.

The state’s cornerstone program for getting patients — and the funding supporting them — out of state hospitals also showed little promise, Rosenn wrote.

Called the Community Hospital Integration Project Program, or CHIPP, it was established in 1991 to preserve the dollars used to run state hospitals for use in the community.

But while it initially identified concrete goals and benchmarks — such as downsizing the system by 250 beds a year and closing the civil wings of three hospitals — the department “inexplicably” failed to follow through on the steps laid out to reach them, Rosenn wrote.

CHIPP was never intended to be the last word on what the commonwealth planned to do in serving Pennsylvanians with mental illness, the state argued. It was just a first step. In fact, it was a framework for future steps.

But Rosenn wasn’t convinced and pushed the state to act, not just plan: “General assurances and good-faith intentions neither meet the federal laws nor a patient’s expectations.”

Raising Robert was easy.

Sue remembers a meticulous kid who was careful about maintaining his curly hair, but effortless in the way he moved through his life.

A natural student, his name regularly appeared in the local paper alongside other classmates who made the honor roll.

A gifted, third-generation athlete, he stunned spectators when he won a match against competitors more than twice his age.

A good brother, Robert teased his siblings, who unlike him, needed reminders to grab their backpacks and do their homework.

Sue was there for it all. A self-admitted helicopter parent, the single mom chaperoned every field trip and went to all the games and competitions and recitals, content to sit in the audience by herself if it meant supporting her children.

If the kids forgot their gym clothes or an assignment, and Sue knew they’d have to miss recess to make up for the infraction, she’d miss work to take whatever they needed to school.

“If they were having a bad day, I was having a bad day,” Sue said.

Robert, the oldest, made the constant effort feel worth it. “Everyone loved him,” Sue said, “the kids and the older people.”

At his competitions, he would sign autographs on frisbees and hats and throw them into the stands. On errands around their small town, he was like the mayor. “Everywhere we went, they'd be yelling, ‘Hey, Robert! Curly, hey!’ And I'd say to Robert, ‘Who's that?’ And he'd say, ‘I don't know.’”

He spent summers swimming at the nearby lake and occasionally at his aunt’s pool with his siblings and his cousin Jonathan. He was a good friend and son, a rock for Sue, especially after she divorced his father early in his childhood.

He graduated high school with honors, enrolled in a nearby university, and began working toward a degree.

His next 20 years seemed as certain as his first.

Despite Rosenn’s misgivings, Pennsylvania made progress in the years following his ruling.

In 2005, the state published “A Call for Change,” a 74-page document describing the radical transformation needed in the mental health care system.

In the years after, officials brought together the people who would need to buy into closing state hospitals — providers, advocates, unions representing hospital workers, and most crucially patients with lived experience.

And for a short while, CHIPP worked.

Under former Gov. Ed Rendell, Pennsylvania closed three more hospitals: Harrisburg in 2006, Mayview in 2008, and Allentown in late 2010.

Following each closure, funding for community supports increased.

People with jobs as providers or staff within the institutions took other positions within the state government. Those with lived experience managing a mental illness found jobs as peer specialists, working with people still in crisis. The state also formalized standards for community treatment teams: groups of mental health staff that would mobilize to help people with complicated and serious needs.

Those days were extraordinary, said Joan Erney, who oversaw the hospital closures as deputy secretary of the Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services.

It was joyful, she said.

“I think that we all felt extraordinarily optimistic about the future of the program.”

In 2009, President Barack Obama directed the U.S. Department of Justice to prioritize enforcing the Olmstead decision. Shortly after, Pennsylvania published its first Olmstead plan, a written blueprint for how the state would build on the momentum.

The document outlined the kinds of goals and deadlines Rosenn had wanted to see state officials commit to.

Slightly less ambitious than prior plans, the new one nevertheless showed the state’s commitment to progress: It would use CHIPP to close 90 beds a year. The state funds previously used to support those beds would continue to flow into the community. Counties would develop their own mini versions of the plan to ensure follow-through.

The next 10 years seemed as promising as the last.

Slowly, and then all at once, Robert started to change.

He had always been health-conscious, Sue said, but his preferences grew peculiar.

He started avoiding the microwave and eyeing his mother suspiciously when she used it. Robert’s once-diligent grooming regimen of showering and changing clothes multiple times a day began to slip.

His first year of college became stressful when he became a father. Robert was the same age as Sue when she had him.

Then, his cousin Jonathan died.

Jonathan met up with Robert while visiting home during his first semester in college. On his way back that night, Jonathan fell asleep at the wheel and drove off the road. Robert was likely one of the last people to see him alive.

Looking back on the decade that followed, Sue sees this moment as an inflection point in not only her son’s life but her own. As grief and guilt began to unravel her son, navigating Pennsylvania’s disjointed mental health system began to unmoor Sue.

Months after Jonathan’s crash, Robert was in one of his own. The resulting DUI led to a stint in a nearby rehab. The structure helped, Sue said, and Robert became a leader at the facility, helping clean out the chapel so he and the other people enrolled in the 12-step program could have somewhere to pray.

But even when Robert was sober, emotional hardships would trigger setbacks, Sue said.

She watched as the corkscrew curls Robert maintained so carefully as a teenager grew long and tangled. He dug a crater into his palm, convinced pencil graphite embedded in his skin from some long-forgotten schoolyard shenanigans was causing his mind to betray him.

As Robert began to cycle in and out of paranoia and psychotic breaks, the next years of Sue’s life became dominated by unspeakable choices.

Should she help her son, even as he burrowed further into distrust and sent her texts full of bile and accusations? Should she spend her days and nights on the phone with the county mental health office, with lawyers, with the governor's office, with kind but unhelpful people who told her over and over, “I’m sorry” and “the system is broken” and “this is just the way it is?”

Or should she give up?

Should she lock her doors, stop the phone calls, and let her son continue to sink into destabilizing paranoia, whatever the consequences?

Should she let Robert go?

Former Gov. Tom Corbett’s 2013 budget was catastrophic for county mental health departments.

The 2008 economic recession had taken its toll on Pennsylvania. State revenue plummeted when the market crashed, and by Corbett’s second year in office, federal stimulus dollars had dried up. Left with state spending in excess of the revenue coming in, and unwilling to raise taxes on state residents, Corbett took a hard-line on spending.

He initially targeted Pennsylvania’s public schools and universities, but uproar following the proposed cuts sent Corbett and the Republican-controlled General Assembly searching for other targets. They found them in social services for groups with less political capital, among them Pennsylvanians with severe mental illness.

He stands by those choices.

"The 2013 budget decisions, made over a decade ago, reflected the economic realities of that time,” Corbett told Spotlight PA in a statement. “We aimed to balance compassion with fiscal responsibility, and I stand by the tough but necessary decisions we made to steer Pennsylvania through a fiscal crisis.”

Nevertheless, the results were devastating.

For years, Pennsylvania has required counties to provide mental health services but provided most of the funding to do so. Alongside the money the state sent counties as it closed hospitals, it also provided so-called base dollars. That funding allowed counties to create services for vulnerable people who either do not qualify or are not signed up for medical assistance.

The dollars also fund services, such as housing, transportation, and case management, that aren’t covered by private insurance and public medical assistance but can be crucial for people who have serious mental illness.

Before the Corbett cuts, that funding flowed through a discrete program alongside funding for other social services. To lessen the blow, the administration offered a block grant that combined the programs, creating one cash infusion counties could use for different needs.

For counties that chose to use the grant, the flexibility provided some help but couldn’t paper over the reduced funding.

But even as voters, frustrated with the austerity of the Corbett administration, selected Democrat Tom Wolf to lead the state, the money did not return.

With fewer dollars, counties offered fewer services and reached fewer people.

As progress toward the grand vision slowed, a tension emerged.

The state had a federal mandate to sunset its inadequate state hospital system.

The county governments, mental health administrators, and clinicians needed somewhere to place the most serious patients, the ones their increasingly meager services could not fully support.

And there were fewer of those beds than ever.

“Put her on the fucking phone.”

The blood was pounding in Sue’s ears, her hard work evaporated by a shower and a book.

Robert had been kicked out of another treatment facility. Convinced electricity was poisoning him, he ripped outlets from the walls. Or had he thrown the vacuum? Or was this the one where he mopped the carpet?

The cycle was always the same regardless of the details: Robert, unable or unwilling to find mental health services, checked into a drug and alcohol treatment facility. Without appropriate psychiatric care, he behaved erratically, sometimes violently. The facility, unwilling to keep him in treatment, took him to the hospital. Once there, he’d be held temporarily but discharged to the street relatively quickly, where he’d call Sue to pick him up.

This time, though, she’d worked with a case manager at a nearby hospital, who pulled strings to find Robert placement in an inpatient mental health treatment program near Philadelphia.

Maybe they could stop the cycle.

When Robert arrived at the hospital from the treatment facility, he’d been psychotic and covered in feces that he had smeared on the walls. To get him to the program, he’d need to be involuntarily committed. But when the assessor arrived to determine whether he could be, Robert had showered and was reading in bed.

He was stable — for the moment.

Seeing that, the assessor decided Robert was no longer a danger to himself or others. His spot would go to someone else in more apparent need.

“What!?” Sue said she asked the assessor over the phone. “People had to jump through hoops to find placement for him.”

Incensed, she asked the woman if mental illness only affects people who are illiterate.

“I was like, really? That is your deciding factor? He can read?”

Hospital, community, relapse, homelessness. Or worse.

Scott Baldwin has been the mental health administrator for Lawrence County since 2020. Over that time, he’s watched residents repeat this pattern over and over.

But for people with serious mental illness, it’s not just a pattern, “that's the system,” Baldwin said.

In the decade since the Corbett cuts, Pennsylvania has not closed a state hospital — with the exception of the civil wing of Norristown — halting the progress of the late 2000s and early 2010s. But until recently, the state has also not increased funding for community care..

“We make these promises to these people that are coming out of these institutions, and we're given a pittance to be able to support them in the community,” said Miki Drutchal, the mental health administrator for Lackawanna County.

In rural counties with smaller populations spread across wide areas, limited state funds overburden the few existing programs; some even have to share their resources with neighboring counties, further stretching their reach. This in turn affects hiring: Attracting and retaining clinicians in these areas is a struggle, especially as fewer dollars are available to entice them.

“I have to beg providers to come and provide service in Greene,” said Brean Fuller, the county mental health administrator.

In 2024, for the first time in over a decade, struggling counties received more state money for mental health.

Gov. Josh Shapiro proposed and the legislature approved a $40 million increase in county base funding in his first two years in office.

Spotlight PA sent a detailed list of findings to the Department of Human Services and Shapiro’s office. In response, DHS spokesperson Brandon Cwalina sent a statement.

“The Shapiro Administration has consistently proposed new, significant investments in mental health resources across the Commonwealth – and worked in a bipartisan manner with the General Assembly to deliver the most meaningful increases in mental health funding in years,” he wrote.

The statement also highlighted Shapiro’s executive order creating a Behavioral Health Council to improve collaboration between government agencies and others involved in the mental health system.

“We are further working with all involved parties, including counties and the General Assembly, to find short- and long-term solutions,” Cwalina said, “especially prevention and diversion strategies that can help strengthen this system.”

Shapiro has proposed an additional $20 million in his 2025 budget, as well as additional investments in community-based care and step-down programs for people in state hospitals.

So far, the infusions have not reversed years of underfunding.

Spotlight PA partnered with the Lehigh Valley Justice Institute to analyze mental health income and expenditure reports from all 67 counties between fiscal years 2017 to 2023, the most recent year available from the Department of Human Services.

The analysis found counties are doing less with less. Between 2017 and 2023, statewide spending on mental health declined by roughly $147 million. Over the same time, mental health services reached fewer people statewide, declining from about 435,000 people served to under 350,000.

The lack of mental health resources is especially stark in communities, like Lawrence County, that do not have access to one of the remaining six state hospitals.

After Mayview closed in 2008, the county received CHIPP dollars to offset the closure, funds that were expected to be untouchable. But the state slashed that money under Corbett as well, Baldwin said. The few state dollars Lawrence County does receive go directly to long-term supported housing for people who have high-level needs and likely always will. But those beds are limited and expensive, Baldwin said.

If county support isn’t available for someone with long-term need, private facilities may not be an option either.

In a system where high acuity care is largely privatized, Baldwin said, “You'd be surprised how many hospitals will just say ‘This is a difficult case. I can't handle this behavior.’ So, then what?”

When Sue grabbed the knife out of Robert’s hand, the kitchen exploded into chaos.

The state trooper dove onto Robert and Sue, yelling and fumbling for his handcuffs. Unable to grab Robert’s wrists, the trooper shackled his bare ankles.

Sue pleaded as Robert writhed underneath her and beat against the trooper, who radioed for backup.

“He did not go after you or me with this knife,” she shouted, desperate to keep Robert from being shot. “Say it out loud: He was going to slit his own throat.”

The trooper repeated her words, and Sue broke free from her son. The officer pulled his Taser, shocking Robert twice.

But Robert fought on. He managed to get upright, continuing to grapple with the officer. Then Robert lunged at Sue, knotting his fingers in her hair.

The three tumbled through the kitchen door, onto the porch. Officers stood on the lawn, weapons drawn.

Sue screamed to the nearby EMTs for help. Police wrestled Robert to the ground, ripping out the chunks of Sue’s curls still tangled in his fingers.

The medics sedated Robert once, then twice, as he struggled against his mother, the strangers on the lawn, and the chaos in his head.

His body went limp, but his eyes fixed on his mother.

Sue watched the responders load her son into the ambulance, Taser prongs still embedded in his back.

Pennsylvania had an opportunity to help its struggling mental health system.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the state received billions of dollars through the American Rescue Plan Act, funds that supported everything from rental assistance to local infrastructure projects.

In 2022, the state legislature set aside $100 million to support the adult mental health system that had become strained as more and more state residents reported mental health needs during the pandemic.

A commission tasked with studying the mental health system found it not only stressed and disjointed but increasingly replaced by the justice system.

“The Department of Corrections and county jails have unintentionally become the largest providers of behavioral health services in the Commonwealth and are not sufficiently prepared and resourced to meet this population’s needs,” the commission found.

Spotlight PA’s findings back this up.

PrimeCare, a private contractor that provides health care to 37 jails across Pennsylvania, supplied Spotlight PA and the Lehigh Valley Justice Institute with 10 years of mental health care data.

An analysis by the newsroom and the research group found that of people who jail staff screened for mental health needs, more than 60% needed services while incarcerated.

As counties do less with less, the state’s local jails have seen an increase both in the number of detainees needing mental health services and the seriousness of their need, even as jail populations have declined.

The company uses four categories to classify the mental health needs of people in jail, ranging from those with no history of mental illness to those with serious diagnoses and significant needs.

Between 2017 and 2022, the share of incarcerated individuals placed in the two most serious categories grew by roughly five percentage points respectively.

Between 2014 and 2022, the rate of jailed individuals on suicide watch per 1,000 has more than doubled. In the same period, the percentage of the daily adjusted population on psychiatric medication has increased from under a quarter to roughly 40%.