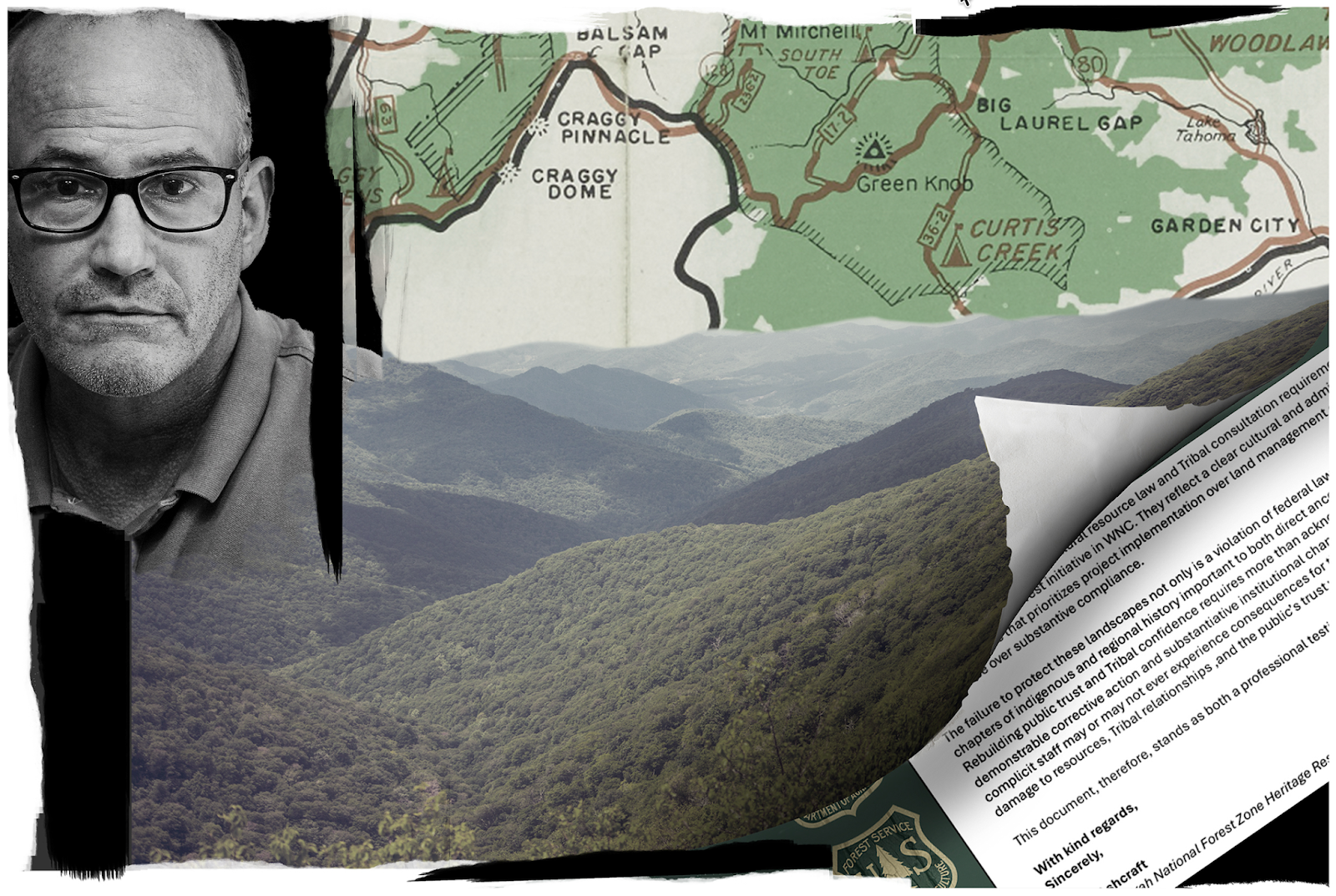

The whistleblower, the Forest Service, and an endless battle in North Carolina’s mountains

Scott Ashcraft warned that the agency was imperiling Native American gravesites and artifacts. Then his three-decade career fell apart.

by JACK EVANS January 25, 2026

On April 22, 2021, 19 acres burned on a sloping face south of Double Knob, a modest peak nestled just south of the Buncombe-Henderson County line. A day later, mountainside still aflame, Scott Ashcraft arrived to document the damage from what would become known as the Seniard Creek Fire.

Ashcraft had been a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist in the Pisgah National Forest for nearly three decades. Assignments like this were routine. But Seniard would prove unusually consequential for Ashcraft: In the five years since the fire, it has become both a site of great scientific promise and a symbol of what Ashcraft describes as a culture of mismanagement, destruction and retaliation.

Over three days, Ashcraft documented enough artifacts, many at an ancient quarry and all dating to the millennia before Europeans came into contact with Native Americans, to come to a tantalizing conclusion.

For decades, the Forest Service has relied on a probability model that suggests most such artifacts will be found in relatively flat areas. This rule of thumb has left steeper slopes, which make up the vast majority of North Carolina’s national forests, largely uninterrogated in any formal sense.

Yet archaeologists’ work in these mountains has often led them past intriguing sites on hillsides — things that, by the model’s lights, weren’t supposed to be there. By 2021, Ashcraft had begun documenting these occurrences whenever he could, developing a theory that the Forest Service’s guidelines had, the whole time, been horribly wrong.

Seniard was steep and artifact-rich, and the damage assessment would open up funding, making it an ideal laboratory for exploring his ideas. Ashcraft brought in leading scientists, who saw the same promise: They believed the site held rich information about the labor, commerce, and spiritual lives of the Cherokee and Muscogee people who once inhabited the land and whose descendants needed to know what they’d found.

“We had an opportunity as a forest to actually do our job and get something really neat and a major, possibly (a) large-scale discovery, documented and described, so that other archaeologists and tribes can use our data moving forward,” Ashcraft said. “It was a great opportunity.”

Today, though, Seniard is a battleground in a yearslong war between Ashcraft and the Forest Service. In a 277-page document shared last month with five tribes — the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, the Catawba Nation and the Muscogee Nation — Ashcraft accused his former employer of failing to protect sites of cultural importance and systemically keeping tribal agencies and the public in the dark. He hopes its release will halt what he alleges are violations of laws including the National Historic Preservation Act, the National Environmental Protection Act and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

The agency’s “internal processes have prioritized expedient project approval over lawful heritage protection and consultation,” he wrote.

The document, styled as a rejoinder to a 2024 report in which the Forest Service largely cleared itself of wrongdoing in a dozen projects about which Ashcraft had raised concerns, is the latest salvo in a fight that has consumed his life.

In 2023, he filed a whistleblower complaint alleging that Forest Service officials were shirking their legal obligations and jeopardizing Native American artifacts as they sidelined science in a rush to get projects done. In the years after, he alleges, he faced a campaign of workplace harassment that spanned colleagues, forest rangers and the top-ranking Forest Service official in North Carolina.

Ashcraft was stripped of projects and responsibilities, including his authority to communicate with tribal officials, with whom he’d developed relationships over many years. In 2024, he was relegated to one of what archaeologists call the “scary rooms,” vast backlogs of uncataloged artifacts dating back decades.

To the Pisgah’s most seasoned archaeologist, the assignment felt like a final betrayal: He retired last March, days short of his 32nd anniversary with the agency.

Ashcraft’s case now sits before the Merit Systems Protection Board, a quasi-judicial agency that handles appeals from federal employees. Even if it rules in Ashcraft’s favor, its authority is limited to his allegations of workplace retribution.

Neither the Forest Service nor several current employees named in Ashcraft’s allegations responded to specific questions for this story. In a written statement, a Forest Service spokesperson said the agency could not comment on personnel matters and “takes concerns raised by its employees seriously.” It noted that the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Inspector General referred Ashcraft’s complaint to the Forest Service, which conducted an “independent review” in which “a team of subject-matter experts found that the Forest Service followed all legal requirements.”

“The Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests are the ancestral homelands of a dozen tribes with enduring connections to these lands,” the statement continued. “Honoring this rich Tribal heritage along with co-stewardship of these lands with Tribal Nations is a top priority for the Forest Service. That’s why we work in close coordination and consultation with Tribal Nations and state preservation officials.”

But Ashcraft’s growing alarm has paralleled the deterioration of the relationship between the National Forests in North Carolina and tribal officials, said Beau Carroll, the lead archaeologist for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ tribal historic preservation office. (Historic preservation officials for the four other tribes that received Ashcraft’s document did not respond to requests for comment.)

For years, Carroll and his colleagues trusted the forest archaeologists to proactively engage them on projects and treat them as collaborators, he said. Recently, though, communication from Forest Service officials has been perfunctory at best, and he believes that in some cases, the agency is falling short of the consultation required under federal law.

Ashcraft’s allegations of destroyed artifacts and marginalized science would be alarming in any context, Carroll said, but both also fit into a much larger picture.

Since the first Trump administration — and especially in its second — tribal officials have witnessed the widespread degradation of important regulations, from the USDA’s plan to repeal the so-called Roadless Rule, which prohibits development and resource extraction in America’s wildest places, to Congress’s recent gestures toward gutting the National Historic Preservation Act’s requirements for tribal consultation. In that context, Carroll said, the failures Ashcraft describes are harbingers of a greater catastrophe.

“They have the dominoes set up,” he said. “They haven’t pushed them yet. I’m just waiting.”

Several other people important to Ashcraft’s allegations declined to comment because they still work for or with the Forest Service. But thousands of pages of documents reviewed by Asheville Watchdog — including legal filings, emails, draft reports, interagency communications and personnel investigations — shed light on the conflict.

They show that officials and colleagues largely dismissed Ashcraft’s expertise and slope-site findings; that they removed him from projects without telling him; that they overrode his scientific opinions and ordered projects to continue despite his concerns; and that they filed workplace harassment grievances against him for alleged violations such as asking questions about projects he’d worked on and responding to emails on which he’d been copied.

They also show that some officials and colleagues found Ashcraft stubborn, prone to missed deadlines and sometimes dismissive of the agency’s bureaucracy, especially once he seized on the slope-site phenomenon.

“(Ashcraft) is an extremely passionate Archaeologist,” the agency wrote earlier this year in an MSPB filing, in which it denied that he had faced retaliation. “So passionate that his emotions and/or beliefs often get the best of him.”

Ashcraft described himself as hyperfocused, intense and sometimes perfectionistic; he could be demanding of colleagues. But all those traits were in service of archaeology done the right way, he said. His battle against the Forest Service has come at the cost of his reputation, his mental health and tens of thousands of dollars.

“I couldn’t live with myself if I always had that overhanging in the background, that I didn’t stand up in the moment,” he said. “That’s far worse than trying to repair my reputation.”

The sites themselves are caught between this battle of wills. Seniard is one of many, but in some ways, it embodies the struggle. On the first page of the new document, Ashcraft wrote that it “has now been fully sabotaged by the Forest Service.”

Among the specialists brought in to work on Seniard was Philip LaPorta, a researcher at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and director of The Center for the Investigation of Native and Ancient Quarries.

He thinks the work there could mark a start to better understanding religious practices and tribal relationships dating back 5,000 years or more. But he believes the Forest Service is uninterested in accepting evidence that would force it to change its presumptions about where artifacts are likely to be found, which puts sacred sites at risk of development and desecration.

“It would be analogous to taking away the churches of a group of people and letting them simply pray in the fields,” he said. “It’s decapitating the culture.”

Ashcraft, 58, was a workaday government scientist, not a big name in the field. And he had come into the profession a little sideways, studying physical geography at Western Carolina University before belatedly recognizing archaeology as his calling. He learned on the job, through a field course with the Office of State Archaeology and consulting gigs, before landing a position at the Forest Service in 1993.

When Ashcraft arrived, the agency’s relationship with archaeology was barely out of its infancy. In 1982, the National Forests in North Carolina hired Mark Mathis, an archaeologist for what was then the North Carolina Division of Archives and History, to evaluate its cultural resources management and map out its future. If there had been any effort to organize the relevant files, he wrote in his resulting report, it had been an utter failure.

Mathis gave the NFNC generalized tools to standardize the agency’s archaeological work. One was a rule of thumb about where artifacts may be found: Level ground, especially near water, was a good bet; any slope of more than 15 or 20 percent, not so much.

The Forest Service still relies on that predictive metric. But Mathis, who died in 2005, never meant for the concept to be a permanent policy. His report noted that two types of important sites – quarries and rock shelters – were quite likely to be found on slopes, and that his model “should be used only for initial planning.” He also said as much to colleagues, said David Moore, a retired archaeologist who worked with Mathis in Raleigh.

“Mark would never have wanted that model to be used without adaptation over 40-plus years,” said Moore, a professor emeritus at Warren Wilson College who was an early mentor to Ashcraft. “The people working on the ground will tell you that there are a lot more potentially significant sites than would be suggested in medium or low probability areas.”

Ashcraft soon learned that the model’s shakiness was an open secret among archaeologists at the NFNC. But his colleagues, he said, were hesitant to suggest to the bosses that they needed to do more intensive surveys, which would make projects slower and more expensive.

David Dyson, a retired Forest Service archaeologist and close friend of Ashcraft, said the dynamic spoke to a tension at the heart of the agency: Specialists tend toward preservation, but the Forest Service stewards the land in order to use it — for recreation and for natural resources such as timber — and prizes efficiency.

“It’s a give-and-take situation, archaeologically,” Dyson said. “I had to accept that, which was difficult. The resistance that I got with everything, it was like, you get the feeling that you’re not wanted here. You’re not part of the program. You’re just an impediment.”

Still, Ashcraft and colleagues made fitful efforts to document slope phenomena. He eventually came to believe that the rule of thumb was backward. Slopes, Ashcraft maintains now, are even more likely than level areas to contain important artifacts. He has seen telltale signs of cultural import on slopes from the edge of the Piedmont all the way to the National Forest land just beyond his own property in Yancey County.

In 2021, Ashcraft came across a geologic jumble under his back deck while renovating his home. The rocks reminded him of what he was seeing at Seniard. The experts he was working with looked at some specimens and concurred: It seemed to have once been a quarry, filled with the remnants of tools used in mining.

The objects also lined up with ones he’d found, along with rock cairns that he believed might mark burial sites, all over the federal land abutting his property. It was all part of one site, he thought: ancient quarries and workshops, covering perhaps a hundred acres or more.

Now he couldn’t ignore the evidence even if he wanted to, he thought. It was right under his house.

There were signs that Ashcraft’s research was gaining traction with some Forest Service officials, especially once the Seniard project was underway.

Wayna Roach, the top heritage official for the Forest Service’s southern region, visited in late 2022. “This work will reframe how archaeologists see the native American lithic traditions of the Pisgah Forest in North Carolina,” she wrote in an enthusiastic internal report. “Further, this work will likely have ramifications much wider than the forest, and will need to be seriously considered by all archaeologists working in the southeastern region.”

In January 2023, Ashcraft’s supervisor, Jason Herron, whose job was to make sure that projects complied with federal environmental laws, sent an email to archaeologists and forest rangers in which he emphasized the significance of the shifting understanding around the slopes.

“At this point, it is reasonable to believe that the sites they are finding are of immense age and contain some of the best preserved artifacts,” he wrote. “It is also reasonable to believe that these sites may have been sacred areas to tribes as they were the direct connection between the land and their tools and ceremonial objects. In this case, these could be very important areas for the tribes.”

By then, LaPorta, the Columbia geoarchaeologist, was involved; so was Larry Kimball, a renowned archaeologist and professor emeritus in Appalachian State University’s anthropology department, who affirmed the veracity and importance of Ashcraft’s findings.

“I went into this very skeptically — like, ‘Yes, Scott, maybe, maybe, maybe,’” said Kimball, whose work involves analyzing the edges of rocks under powerful microscopes to determine if they’ve been used as tools. “Sure enough, they were in fact used, and they were used in a way that he had hypothesized.”

And as word of Ashcraft’s research spread, archaeologists told him that they’d made similar findings in east Tennessee and southwest Virginia.

But Ashcraft still had a hard time persuading decisionmakers and other rank-and-file archaeologists to take what he was seeing seriously.

“His interest is misguided,” Nick Larson, the ranger overseeing the Pisgah’s Grandfather Ranger District, told a Forest Service investigator in 2023.

“He sees things he believes are artifacts however other archeologists agree that these are rocks and are not humanly altered,” another Forest Service archaeologist told the same investigator, according to an agency document.

“The general idea floating out there is that no one else can see what you are seeing,” Roach told Ashcraft in a 2024 email urging him to extricate himself from the Seniard project. “So any movement toward others … to be able to ‘learn’ to see those things as well is totally a win.”

In 2021 and 2022, the NFNC had worked to revise its programmatic agreement, which governs how the Forest Service division works with state and tribal agencies. Ashcraft argued for the Mathis model to be thrown out, as did his counterpart for the Nantahala, an archaeologist named Shawn Jones, who wrote in an internal document that testing on low-probability landforms should be expanded, as “sites within the low probability landforms are underrepresented in the archeological record and have very little defining research to build a base of knowledge and represent the cultural activities taking place within the sites.”

They were unsuccessful. A little over a month after Herron’s email, James Melonas, the top-ranking Forest Service official in North Carolina, sent a letter to district rangers in which he emphasized that the old way of doing business would continue.

“The current PA emphasizes pedestrian survey of the entire project and subsurface testing strategies in high probability areas,” he wrote. “This survey strategy and methodology must be followed.”

The last eight words were underlined.

Three months later, Ashcraft blew the whistle.

In a complaint filed with the Department of Agriculture’s Office of Inspector General, he outlined how he believed the Forest Service was failing to preserve cultural heritage sites and listed a dozen projects that he said had damaged or threatened important areas.

Melonas asked the regional office to review the projects. Though the resulting document never referenced Ashcraft’s whistleblower complaint, it served as a way for the Forest Service to largely absolve itself of his allegations. The initial findings, compiled later that year, found procedural errors in only two of the projects, both of which the NFNC later sought to pin on Ashcraft. In the fall of 2024, it released an expanded version of the report to state and tribal agencies, prompting Ashcraft’s new document.

Carroll, the EBCI archaeologist, said he was skeptical of this process from the beginning.

“If there was a doctor that you suspected of malpractice, would you trust him enough to investigate himself?” he said. “And then would you trust him enough after that to find himself guilty and then punish himself?”

The construction of a network of hiking and mountain-biking trails just north of Old Fort was particularly contentious. A partnership between the Forest Service and a nonprofit, it involved private money and public promises of some 40 miles of trail. The arrangement put pressure on the Forest Service to live up to a timeline committed to the public, a stressor referenced repeatedly by employees in emails shared by Ashcraft and in documents included in the agency’s MSPB filing.

A consultant hired by the Forest Service to survey the area ran out of money before finishing. Ashcraft argued with outside archaeologists, brought in by the Forest Service-nonprofit partnership, who disagreed with his ideas on slopes.

And he and Herron clashed with Larson, who was overseeing the project, and with Herron’s boss, Appalachian District Ranger Jennifer Barnhart, over what they felt were unrealistic deadlines for a report that they suspected would take months of work and several hundred pages to complete. (It was ultimately finished in late 2021. Herron, who later moved to a different position within the Forest Service, declined to comment.)

In the spring of 2022, the Forest Service was supposed to send a revised version of that report to interested tribes and the State Historic Preservation Office, a step that would allow it to construct a parking lot and some trails. It included a recommendation from Ashcraft for close monitoring of construction near a sensitive site.

As internal emails later described, Larson told one of the Forest Service archaeologists working on the report that he would print and mail the documents. They weren’t sent — a fact that only came to light months later, after Larson had signed off on the project.

The state was belatedly informed and, in early 2023, concurred with Ashcraft that the site was important and damage should be monitored and mitigated. By then, it was, as Ashcraft wrote in his recent report, “buried underneath the trailhead and parking lot area.”

“It appears that the NFsNC holds itself to a different standard than that applied to private individuals or looters,” Ashcraft wrote. “No person caught damaging or destroying archaeological site contexts could plausibly claim their actions were a ‘procedural error’ and avoid legal consequences.”

Later, according to documents included in the Forest Service’s filing in Ashcraft’s MSPB case, Larson told a Forest Service investigator that the whole thing was Ashcraft’s fault. Larson had made the call to begin construction without having all the necessary approvals, he admitted, but the problem was “rooted in Scott’s inability to complete the report and consultation in a timely manner.” Larson didn’t mention that the documents weren’t sent. (The investigator did not find Ashcraft at fault.)

Another conflict involved a wildlife clearing near Devil’s Courthouse, proposed as part of a larger project in the early 2010s. Ashcraft and others had surveyed the area then, but they didn’t look at spots, including the land slated for the clearing, that had been surveyed as part of a late 1980s timber project. Over time, the Forest Service lost confidence in many old surveys, so when a specialist on the project asked Ashcraft to tag along in early 2023, he thought it a good idea.

He found enough artifacts that he thought a thorough survey was in order. In Cherokee lore, Judaculla is a giant who rules over hunting practices and game animals, and the cave below Devil’s Courthouse is his home.

“I had intended to find a way to push this forward right now, but the artifact recovery became enough to persuade me into caution,” Ashcraft wrote in an email to another specialist on the project in February 2023. “I wish I had better news for moving forward immediately with this (wildlife clearing) construction, but it’s the process we are supposed to go through.”

Two months later, in April 2023, the ranger overseeing the project, Dave Casey, emailed Ashcraft. “I made the decision today to move forward with the wildlife opening,” he wrote. He cited the surveys from more than a decade earlier that had left out the area. A letter from Casey to the SHPO showed that he’d actually made the decision a month earlier.

That May, Casey told other employees to go ahead with the wildlife clearing. The silviculturalist who’d gone to the area with Ashcraft was puzzled.

“Are you telling us to move forward with implementation without the arch survey and documentation?” she asked.

“Yes,” Casey responded, “I’m saying to move forward without any additional arch surveys or documentation.”

Ashcraft heard through the grapevine months later that another archaeologist had been to the area and found nothing. Confused, Ashcraft emailed Casey, asked about the project’s status and offered to give his input. Casey told Ashcraft to turn in any artifacts he had collected from the site. He wasn’t involved in the project anymore, Casey said.

That was news to Ashcraft. Herron, his supervisor, said he hadn’t heard that, either. Casey’s email was how they learned that Ashcraft had been stripped of his assignments: not just the clearing, but every project, aside from Seniard, that he had raised concerns about.

They had all been reassigned to archaeologists in Melonas’s office.

Carroll, who has lived his whole life on the Qualla Boundary, the home of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, was drawn to archaeology in part because he saw it as an opportunity to help develop the story of the Cherokee, a narrative that has largely been told through the lens of extractive outsiders. Finding people who say they’ve worked with the tribe is easy, he said; far fewer are those who can claim a truly reciprocal relationship.

“The way that I know that you actually collaborate with us is that I see you on our front porch at the office,” he said. “And I’ve seen Rodney (Snedeker, Ashcraft’s late boss and mentor) and Scott on that porch a lot.”

That process, at its best, is about far more than a simple consultation between the tribe and the U.S. government, Carroll said. After centuries of colonialism and oppression, tribal histories, tens of thousands of years old, are as patchwork as they are rich. Archaeological findings help fill in the gaps. Consultations give occasion for experts like Carroll to ask elders about specific places.

“It’s like a spider web, because it connects to other stuff, too,” Carroll said — geography and history and medicine and spirituality, all branching and weaving. “A lot of those older people that have that knowledge aren’t around anymore, or they’re not going to be around. … A lot of the stuff that we lost is just gone.”

Compromise is an unavoidable part of Carroll’s work: The EBCI’s tribal historic preservation office has six employees and reviews federally funded projects on ancestral Cherokee territory in eight states — everything from the rerouting of hiking trails to the construction of “hundreds of cell towers,” he said. For every idealistic specialist on the federal side, there’s a boss who wants the job done quickly and cheaply. For years, Carroll said, he and his colleagues could count on the Forest Service archaeologists to keep them informed enough to make the right decisions.

Snedeker retired in 2017 and died in 2021. Around the same time, Carroll said, the relationship between his office and the Forest Service darkened. NFNC archaeologists stopped showing up at the office. The EBCI specialists started hearing secondhand about projects on which they should have been consulted but hadn’t.

Ashcraft has pointed to one key change from that period that he believes was especially disruptive: In 2022, Melonas instituted policy requiring that any communication with tribal and state agencies be channeled through a select Forest Service official. To Ashcraft, the shift seemed intended to keep the tribes in the dark.

The new policy cut off Ashcraft’s permission to talk to the EBCI in an official capacity, but he still called his contacts there to tell them what he was finding on the slopes. Carroll was intrigued. He trusted Ashcraft as an archaeologist, and he could believe that he was on to something.

To his ancestors, Carroll knew, the land’s material qualities — that a spot could make a good quartz quarry, for example — were intertwined with its spiritual aspects, which would determine whether that quartz was useful for infrastructural or medicinal purposes. So much of that land was mountainous; why should those principles apply only to the flat parts?

Still, he said, Ashcraft’s claims were exceptional, in that they flew in the face of widely accepted guidelines. He wanted exceptional evidence. He wanted to see it himself.

Those involved in the Seniard project now see it as a missed opportunity in this regard. Ashcraft asked for an EBCI representative on the team from the beginning; he’s alleged the Forest Service failed to meaningfully involve the tribe.

Kimball, the Appalachian State professor emeritus, believed the findings warranted more research and a recommendation that the site be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places — a process that he said was “pretty standard.”

“But, and this is the big but, there was no consultation with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the tribal historic preservation office there, and they have archaeologists,” he said. “Normally one would bring the people who are most interested in the cultural patrimony — number one, to see what’s out there, and number two, to make their interpretations and preferences known. … That didn’t happen.”

Carroll has been particularly struck by Ashcraft’s descriptions of destroyed rock piles. These features are often assumed to have been incidentally created sometime in the past few centuries by land-clearing farmers — and many are, Carroll acknowledges. But these sites can look quite similar to cairns marking locations of cultural significance, including Native American burial sites, the desecration of which is a major violation of federal law. Telling them apart would take extra work by the Forest Service.

“They’ve been in those forests long enough to know the places where there are cultural resources, when they should consult,” Carroll said. “It’s just, it costs money, takes time, and it keeps them from getting the projects that they want done.”

The Forest Service is aware of this problem. Amid his whistleblowing, Ashcraft came across a relatively obscure document that startled him.

The United South and Eastern Tribes, a nonprofit that represents more than two dozen tribes for political and governmental purposes, had issued a resolution asking federal agencies to do a better job consulting with tribes when it came to “sacred ceremonial stone landscapes,” which had been “used … to sustain the people’s reliance on Mother Earth and the spirit energies of balance and harmony” but which had largely been written off by archaeologists as “the efforts of farmers clearing stones for agricultural or wall building purposes.”

To Ashcraft, the document showed that many of his concerns had been brought forth by the tribes already. He was shocked he’d never seen it. It was signed in 2007.

Here, for the Cherokee, the stakes are clear, Carroll said. Matters involving the dead go beyond any notions of laws or cross-cultural respect. In the Cherokee belief system, death is a contaminant. Failure to approach the dead properly can bring bad luck, illness, more death — not just to the actor but to those around him. It spreads like a virus, and it threatens everyone.

“We’re trying to protect everybody — ourselves, the people that are working — because we believe there’s real, serious implications for doing things,” Carroll said. “There’s always a consequence. And there’s no way for us to mitigate that, especially if nobody’s asking us what those are.”

Ashcraft now sees the termination of his authority to talk to the tribes as a prelude to what he has described as a sustained campaign of workplace harassment. In January 2023, days after Herron’s supportive email about Ashcraft’s slope-site findings, Barnhart filed a harassment complaint with the Forest Service, alleging that Ashcraft had become known for “explosive outbursts” and lashing out at colleagues in after-hours text messages.

Ashcraft had texted colleagues outside work hours, he admitted to an investigator, and he’d had one heated conversation with a fellow archaeologist, to whom he apologized the following day. But he denied that he made a habit of it. Ashcraft ultimately received a written warning but no punishment.

Between September 2023 and April 2024, Ashcraft’s bosses and colleagues filed five more such grievances. They complained to investigators about hearing from his lawyer regarding the whistleblower case; about him having a lawyer at all; about his questions about projects he didn’t know he’d been removed from; about him responding to emails on which he’d been copied.

In none of those cases did investigators find any wrongdoing by Ashcraft. But only once did the Forest Service tell him so.

He had one consistent ally in his supervisor, Herron. In the summer of 2023, Herron recommended Ashcraft for a $1,000 performance bonus; Melonas denied it, according to internal documents, citing his dissatisfaction with the Seniard project. At the end of that year, emails show, Herron sparred with Barnhart when she demanded he give Ashcraft a poor performance review.

Soon after Herron moved to another job within the Forest Service in 2024, Ashcraft’s supervisors reassigned him to organize a backlog of artifacts that he and other archaeologists had collected over decades. The Forest Service has contended that this was an important task, not a demotion.

But Ashcraft thought the message was clear: For an archaeologist late in his career, being assigned to the “scary room” was a professional death sentence.

Some of Ashcraft’s work has continued without him. A draft of a report on Seniard, completed in 2024, ended by describing the site as a “complex natural and cultural landscape” and “a singular example of this type of poorly documented cultural resource, which only reinforces the need to develop ways to identify, evaluate, and manage such complex sites.”

But Ashcraft is not optimistic that the slope-site findings will be taken seriously. He said he was told by the contractor finishing the project, Paul Webb of TRC Companies, that Forest Service officials had pushed him to de-emphasize slope-site findings in the final report. Webb declined to comment, but early 2024 emails he shared with Ashcraft show that Casey, the forest ranger over the project, questioned whether Seniard had cultural significance or was simply “natural rock within a mountainous landscape.” Ashcraft has also alleged that the Forest Service persuaded Webb to change a recommendation of the site’s eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places to ineligible.

LaPorta said in an interview that, as far as he knows, the outside specialists’ findings — including a new probability model to help locate and identify high-elevation quarries — have been largely written out of the final report, which has yet to be released.

“We did all the work,” he said. “And the work is stuffed into an appendix no one will ever see.”

The Seniard project area borders private land and has no public trailhead. Other sites are more accessible. One afternoon this fall, Ashcraft and Dyson parked near a trailhead and ascended into the hills outside Old Fort.

After a few minutes, they passed a ravine, choked with rhododendron. It looked as elemental as any of the surrounding slopes and ridges. But this gash in the mountain was manmade, Ashcraft said — a quartz mine dating back some 10,000 years. Buried under the earth’s surface, he believed, was millennia of cultural refuse, and perhaps more. This was hard, dangerous work. It stood to reason that there would be gravesites nearby.

Farther up the trail was the site that Ashcraft and Dyson had come for. On the upward slope to their left, stacks of wide, flat rocks peeked from behind roots. Pieces of stone studded the trail and the downslope to their right. Based on his reconnaissance and conversations with experts, Ashcraft believed the area had once featured a series of terraces and walls. This was the type of feature he had tried to warn forest officials about. It looked to him like a trail crew had plowed through it, then used the debris to shore up the trail.

“It’s not their fault,” he said. “It’s the Forest Service management’s fault for not listening. The trail crew didn’t know any better.”

Ashcraft scrambled up the slope, where he pointed out a circular heap of rocks; another sat nearby, still covered by autumn detritus. He suspected they were burial cairns. A few feet away, a hunk of metal and rotting wood jutted from the forest floor. Ashcraft recognized it.

“That’s my tool!” he said with a smile.

He’d surveyed this area four years earlier, frantically documenting as many artifacts as he could, and left it behind in his haste. Now it seemed almost a piece of the landscape, a distinctly modern implement juxtaposed with the millennia-old cairns. This piece of forest had been left enough alone for so long that the now and the long-ago could rest side by side. The undisturbed place was what bridged the vast gulf between points in time. He was desperate to keep the tether from fraying.

“That’s my gift, my offer to the site,” Ashcraft said, gesturing at the tool. “It stays right there.”

Asheville Watchdog welcomes thoughtful reader comments on this story, which has been republished on our Facebook page. Please submit your comments there.

Asheville Watchdogis a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and Buncombe County. Jack Evans is an investigative reporter who previously worked at the Tampa Bay Times. You can reach him via email at jevans@avlwatchdog.org. The Watchdog’s reporting is made possible by donations from the community. To show your support for this vital public service go to avlwatchdog.org/support-our-publication/.